Re-enchanting Our World: Haejoang Cho on Memory, Hallyu, and Mutual Care

Haejoang Cho is a cultural anthropologist, feminist, Professor Emeritus at Yonsei University, and founder of Haja Center (The Seoul Youth Factory for Alternative Culture). Across her many decades of work, Cho has traced how gender roles, youth subjectivities, and constructions of national identity have shifted as Korean society underwent colonization, compressed modernity, and neoliberal economic restructuring. For Issue 002, we talked to Professor Cho about Hallyu’s sociocultural origins and the political possibilities that it holds in our contemporary moment.

The Story of A Colonial Subject Who Remembers Through the Body

Professor Cho, you have been studying the Korean Wave since its early development in the 1990s. I’d love to hear about what this means for you personally, so let’s begin with your story. Can you introduce yourself to MENT’s readers?

Sure. I have lived on this planet for 76 years, so an introduction seems necessary. I am a 76-year-old anthropologist born in 1948 in Busan, South Korea. This was three years after Korea’s liberation from Japanese occupation. After the Japanese occupation, the peninsula was divided into North and South under the so-called protective occupation of the US and the Soviet Union.

I was only two when the Korean War broke out, but living in Busan spared me from witnessing its horrors firsthand. Instead, I spent my childhood surrounded by displaced intellectuals and artists, who were eager to educate their children into citizens of a “modern” nation. I was one of the children blessed by their enthusiasm. Growing up, I read Western children’s books, took ballet classes, learned the piano, and even joined the children’s choir at a broadcasting station. When I moved to Seoul in middle school, I was ready to become a “modern” youth and enjoy the city’s affluent cultural life.

Growing up in a patriotic family, I always believed that I should dedicate my life to the betterment of Korea. I decided to become a historian so I can understand the injustices of our world and use that knowledge to help create a better one. In 1971, I went to the US to study cultural anthropology. My doctoral research focused on Jeju haenyeo, the female freedivers who made their living by harvesting seafood and seaweed from the ocean.

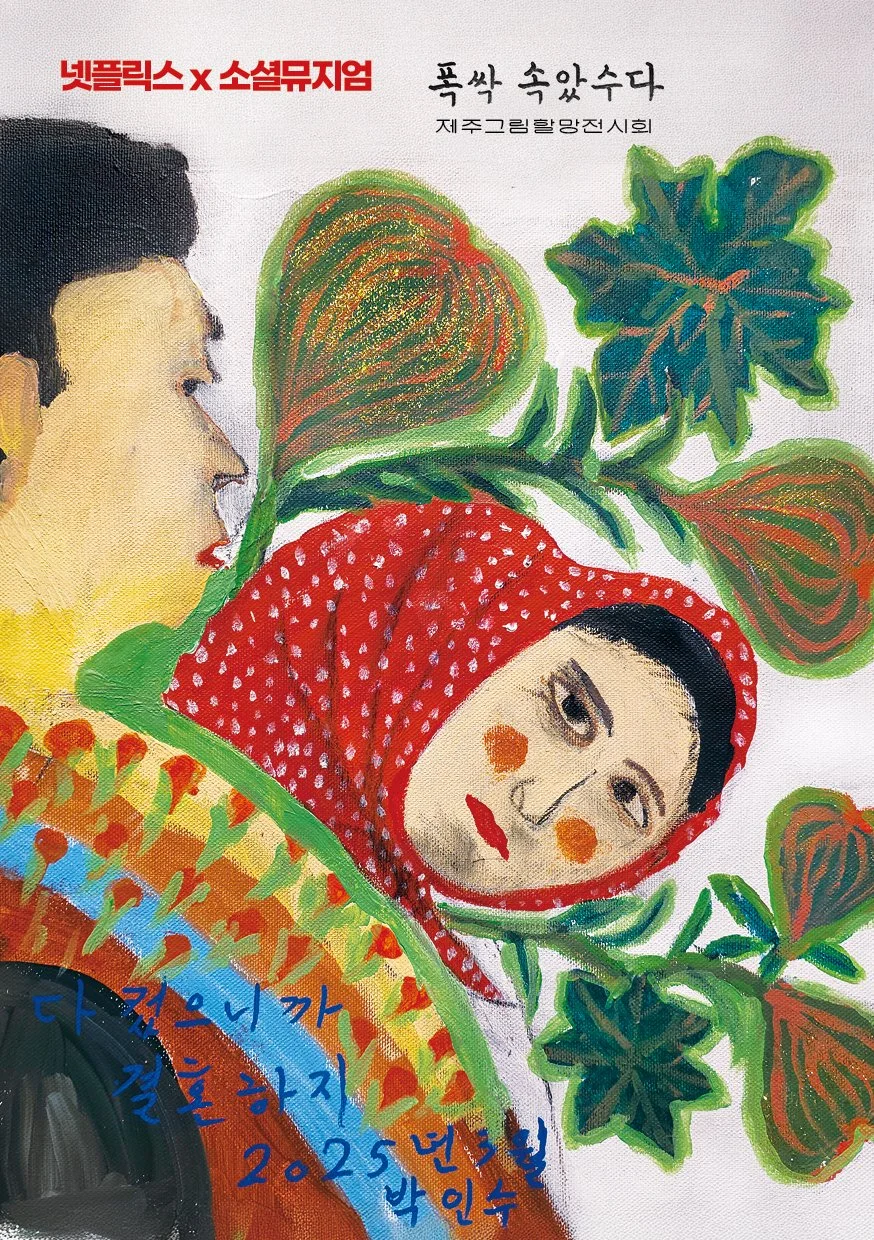

After graduation, I returned to Korea and taught at Yonsei University for 35 years. I have since retired and now live in Jeju’s Seonheul Village. The village is known for our geurim halmang (grandmothers who paint)—grandmothers who retired from physical labor and now paint, having converted their farm sheds into mini art galleries. Recently, the grandmothers received attention for painting scenes inspired by the K-drama When Life Gives You Tangerines (2025), which is largely set in Jeju and depicts Korea’s tumultuous path to modernization through the perspectives of ordinary people.

Today, we no longer live in a “modern” world. Instead, we live in a perilously postmodern and posthuman era. So I came to Seonheul Village thinking of it as my Noah’s Ark. Even here, I continue to observe people and participate in community activities as a “native anthropologist” who is eager to help create, if possible, a less destructive world.

Korea: From Cultural Colony to Cultural Exporter

Can you describe Korea’s media environment in the 1950s and 1960s? Growing up, what were the forms of popular culture available to you?

The American military presence in South Korea began after Korea’s liberation from Japan, and this led to an influx of American cultural products. During the 1950s, yeoseong gukgeuk—a reinvented genre of traditional Korean opera featuring an all-female cast, and recently depicted in the K-drama Jeongnyeon: The Star Is Born (2024)—had been popular in Busan, but that soon faded. After the Korean War, the film industry took over the entertainment world, and people who were struggling in their everyday lives looked for solace in the cinemas.

I remember watching A Farewell to Arms (1932), Gone with the Wind (1939), Waterloo Bridge (1940), High Noon (1952), and other Westerns starring John Wayne. Korean filmmakers who had been trained in the Japanese film industry during the colonial period also became active after liberation, producing a wave of high-quality films. I remember watching Shin Sang-ok’s The Houseguest and My Mother (1961) and Kang Dae-jin’s The Coachman (1961) with my grandfather, who always shed tears during the sad scenes.

When black-and-white TV came out, I was in high school. There were no Korean dramas yet. Instead, I was deeply engrossed in the American soap opera Peyton Place (1964). I still remember Mia Farrow’s enigmatic presence in that show, as she walked in the dark streets with a pile of books in her arms. The drama depicted a shadowy town full of illicit relationships, which I found unfamiliar and uncomfortable. The cultural gap was vast, but I admired Western culture and interpreted it on my own terms.

Through radio, I fell in love with Sue Thompson’s “Sad Movies” (1961), and I remember writing down the lyrics in Korean and singing along until I memorized them. I also passionately sang Patti Page’s “I Went to Your Wedding” (1952). In my third year of middle school, I went with friends to a music café in Myeongdong just to listen to The Beatles’ “Yesterday” (1965).

In that era, many Korean pop singers had listened to American music over the American Forces Korea Network (AFKN) and got their own start performing in US military camp shows and clubs. As radio and television became more widely accessible in the 1960s, these Korean performers began to gain mainstream recognition. Musicians like the Kim Sisters, the Pearl Sisters, Patti Kim, and Shin Joong-hyun’s rock band Add 4 developed strong fan bases and became some of the most popular musicians of the time.

The Kim Sisters began their careers performing for American soldiers in US military camps in South Korea. Later, they were invited to the US and performed on the Ed Sullivan Show.

By the 1970s, youth culture was thriving in Seoul’s Myeongdong district. Lee Byung-bok, a stage artist who had just returned to Korea after her studies at the University of Sorbonne in Paris, opened Korea’s first small theater “Café Theatre.” I became a regular there. New bars, cafés, and beer halls played Western pop music, and local folk singers with acoustic guitars—artists such as Song Chang-sik of Twin Folio, Kim Min-ki, Yang Hee-eun, and Hahn Dae-soo, all now considered the pioneers of K-pop—also performed there.

As a university student, I spent a lot of time in these places. Just as today’s youth are growing up amidst the wave of Hallyu, I grew up amidst an American cultural wave, though those influences were already sowing the seeds for an emerging Korean pop culture. In 1971, I graduated from university and went to the US to study. When I returned to Korea in 1979, I found an explosive local music scene. The folk musicians were flourishing, and rock bands like Shin Jung Hyun & Yup Juns, Sanulrim, and Songgolmae were also active during this time.

Most of all, college song clubs were gaining in popularity—and they were all singing in Korean! Having mostly sung English-language songs before, I found Korean-language ballads and rock music both unfamiliar and deeply moving.

Korea’s Spirit of Resistance

That was in the 1980s, right? Now, nearly half a century later, the Korean Wave has positioned itself at the heart of global pop culture. What do you think facilitated Korea’s transformation from a cultural colony to a nation that produces and exports culture?

South Korea’s rapid economic and technological development played a key role in the emergence of cultural industries in the mid-1990s. The digital revolution also facilitated the rapid dissemination of cultural content.

But aside from these necessary conditions, which have been amply documented, I think a key sociocultural factor lies in Korea’s historical struggles. Korea has historically been a small nation within the vast Sinocentric world order. The country had to make extraordinary efforts to maintain a degree of independence and autonomy, never having experienced a prolonged era as a dominant power. Korea’s struggle to escape poverty was exacerbated by the turmoil of the late Joseon Dynasty and the colonial period under Japanese rule, ultimately reaching its peak with the devastation of the Korean War. Such historical struggles nurtured a spirit of resistance that I believe served as fuel for the global spread of the Korean Wave.

How have you seen this spirit of resistance manifest?

As is well known, South Korea was ruled by successive military dictatorships after the Korean War—first under Park Chung-hee, who came to power in a 1961 military coup, and then under Chun Doo-hwan, who seized power in 1979 after Park’s assassination. In 1980, the Chun Doo-hwan regime violently suppressed Gwangju citizens’ protests against martial law, an incident dramatized in Han Kang’s Human Acts.

[Editors’ Note: See Yoojin Kim’s piece on Gwangju’s literary and material memoirs in this issue.]

As news of the Gwangju Massacre spread, anti-dictatorship struggles broke out among ordinary citizens. Many university students participated in this political resistance. In 1979, I returned to Korea from the US and took a university faculty position. I found that students were not attending regular classes but holding their own seminars and participating in street demonstrations, chanting the words “Overthrow the dictatorship!” The student demonstrations developed into a nationwide civic movement and finally ended the military dictatorship in the spring of 1987. The democratic citizens of Korea experienced a great victory.

Meanwhile, beginning in the mid-1980s, women began protesting institutionalized gender discrimination, including the hoju system—which only allowed men to be heads of family—and the “marriage retirement” system, which required that women resign from their jobs upon marriage. Women published their own magazines and organized events such as the Anti-Miss Korea and Menstruation Festival. Around that time, I formed a group called Another Culture with fellow professors, students, writers, and office workers. We held feminist seminars and published magazines and books that became popular, selling over 10,000 copies each time.

I believe that these struggles of the 1980s and 1990s, where citizens joined forces against injustice and sought to write a new history, laid the foundation for a solid civic consciousness.

How did these political struggles pave the way for Hallyu’s emergence?

As youths were participating in political struggle in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Soviet Union dissolved and the Socialist Bloc collapsed. Student activists who had been inspired by Marxism lost their direction, and youths began to engage in social movements centered on freedom, self-expression, and self-realization. This “New Generation” of youths drew on creative tactics to resist the authoritarian educational system. They skipped school and formed indie bands, roaming the streets and dancing in clubs with their baggy pants, dyed hair, and body piercings.

In 1992, Seo Taiji and Boys burst onto the music scene with songs that encouraged youths to challenge the establishment and create their own world. This marked the beginning of K-pop as we know it. Film and theater also thrived under the freer political climate of South Korea’s newly democratized government. Bong Joon-ho and Park Chan-wook both made their first films during this time. In television, dramas like What Is Love (1991) and Jealousy (1992) depicted a world no longer solely centered around the patriarchal family, while Sons and Daughters (1992) confronted head on the issue of Korean gender inequality. Sandglass (1995), which provided an intimate look at the ordinary lives tragically upended by military dictatorship, captivated the entire nation.

Women and young people who wanted to become free individuals appeared on the stage of history. They set out to create their own lives as creative subjects, breaking away from the era of authoritarianism. It was the beginning of a movement to recover what Habermas described as the “lifeworld,” the sphere of everyday life that had been colonized by repressive systemic mechanisms.

Haja Center: An Autonomous Zone for Youth

A brief introduction to the Haja Center

In 1999, you founded the Seoul Youth Factory for Alternative Culture, also known as the Haja Center, to provide a space for youths to pursue their own ideas and interests. Can you tell us about the genesis of Haja Center and the role it played in recovering South Korea’s lifeworld?

During the historical transition of the 1980s and 1990s, I came to realize that we must urgently focus on not only the women’s movement but also the youth movement. Suicide rates among teenagers were increasing due to the stress of exam-oriented education. Large number of students began to express their discontent by disrupting the classroom in a movement called “school collapsing.” I organized a research group on school dropouts and participated in the presidential government committee for education reform. My sense was that while institutional reform was necessary, alternative models should be created. The Seoul Metropolitan Government agreed and entrusted me with the task of establishing a new youth center in collaboration with Yonsei University. Hence, the Haja Center was born. In Korean, “Haja” means “Let’s do it!”

Teenagers who wanted to do something other than struggle for college examinations crowded into the Haja Center. Supported by professional staff and furnished with co-working studios, Haja provided young people who were interested in creative writing, pop music, web design, and filmmaking with an autonomous space for cultural experimentation. These youth were not confined to the studio spaces within the Center but frequently collaborated with activists and artists from Hongdae’s underground indie scenes, forming close relationships and growing through shared projects and experiences. In many ways, the Haja Center was a radical experiment in creating new models of youth engagement—an experiment that might have never emerged if not for the shock of the 1997 IMF Crisis.

One of Haja Center’s notable alumni is Moon Ji-won, the screenwriter of the acclaimed 2022 K-drama Extraordinary Attorney Woo. Haja graduates have gone on to make their mark across different sectors of the cultural industry, including in hip-hop, theater, film, television, and design. Renowned rapper The Quiett is a former member of Haja’s hip-hop studio, and a few years ago, his fans visited and donated to the Center in celebration of his birthday.

A conversation between Haejoang Cho and Moon Ji-won, screenwriter of Extraordinary Attorney Woo and a Haja Center alumnus.

Today, the experimental atmosphere that once defined Haja may be harder to find, but many of the Center’s former students remain active in fields connected to the Korean Wave.

From Cultural Revolution to the Neoliberal Wave

You mentioned the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, also known in South Korea as the IMF Crisis. What role did this play in the cultural revolution of the 1990s?

Many of the era’s cultural experiments, including Haja, were fueled by a shared national will to overcome the crisis brought on by the IMF bailout. For about a decade after the IMF crisis, before the full force of neoliberalism swept in, South Korea underwent a unique period of grassroots transformation. The country recovered from the crisis through collective effort, and the outstanding performance of the national football team during the 2002 World Cup inspired tremendous confidence. During this period, young people and women led alternative educational movements, cultural projects, ecological activism, and a wide range of indie and underground initiatives.

Key figures of the Korean Wave—such as the director Bong Joon-ho, screenwriters Kim Eun-sook and Kim Eun-hee, and the founders of the “Big 3” K-pop entertainment agencies—came of age during this era. They developed their organizational skills through the Democratization Movement of the 1980s and honed their expressive capacities in the cultural ferment of the 1990s.

But things have changed dramatically. As neoliberalism becomes more dominant, the sociologist Hong-Jung Kim has argued that modern Korean society is driven by what he calls “survivalism”—a collective mentality and an affective regime that prioritizes survival above all else. This mindset, Kim contends, is what enabled Korea to navigate not only war, but also dictatorship, democratization, and rapid economic growth. Today, the entertainment industry is also shaped by a survivalist logic of “win or perish.” The intense discipline and relentless self-training exhibited by contemporary idols and actors stems from this entanglement of neoliberalism and survivalism.

The Korean Wave has become a massive industry. Of the roughly one million aspiring idols, only around 300 achieve stardom. Watching K-pop audition programs is like watching Squid Game—a brutal competition where contestants pour their entire beings into the performance, and the last one standing emerges as a lonely hero. Behind the glamorous global stars lies the creation of a vast underclass. This is the reality of Korea’s so-called “Sampo generation,” a term describing youth who have given up on dating, marriage, and childbirth. Economic precarity and existential anxiety have fueled gender conflict, giving rise to increased misogyny and gender-based violence.

Is today’s Korean Wave the ultimate triumph of neoliberalism, then? Back in 2005, you raised concerns about the commodification of Hallyu.

Yes, 20 years ago, I asked if Hallyu should be understood as culture or as commodity. In truth, it is both. Some of the early K-pop music videos featuring girl groups bordered on the pornographic. Many dramas were also extreme in their sensationalism. These were made purely to sell, and I wasn’t sure they had staying power.

But it’s complicated. Today, the “K” in K-wave has become more than just an abbreviation for Korea. It’s a genre and a brand in itself, functioning as a shared language that connects people around the world. Whether this phenomenon is a gift or a destructive force is hard to say, especially as the world enters an era marked by escalating conflict and imminent collapse.

That said, I do believe that Korean pop culture still holds potential for challenging neoliberal survivalism. At the very least, it offers comfort and solidarity for people on the peripheries of the world system. Many K-dramas revisit themes of anti-colonial resistance and democratic struggle. Perhaps those who have experienced imperial violence or authoritarian rule in their own regions find something familiar and inspiring in these stories. These stories point toward something beyond mere survival—toward resilience, hope, and transformation. And we see these everyday forms of resistance not only on screen, but also in real life.

When Life Gives You Tangerines: Mutual Care in a Time of Precarity

In my own work, I’ve been particularly interested in K-dramas that explore how quotidian communal life becomes a site of resistance against broader structures of oppression. I’m thinking of shows like Misaeng (2014), Dear My Friends (2016), My Mister (2018), When the Camellia Blooms (2019), Our Blues (2022), My Liberation Notes (2022), and the recently concluded When Life Gives You Tangerines.

Speaking of When Life Gives You Tangerines, I saw that the Netflix production team recently visited Seonheul Village to film the grandmothers as they watch the drama. The grandmothers’ joy feels like a real-life example of the kind of healing and resistance that becomes possible when people come together to do what they love, much like what the Haja Center fosters for young people. Can you tell us more about Netflix’s visit to Seonheul Village?

The Netflix promotional team learned about these grandmothers and, as part of their campaign, proposed filming the grandmothers watching the first two episodes of the show. Since they didn’t have access to Netflix at home, the grandmothers gathered at my house to watch the episodes together. Their reactions—laughter, tears, and quiet nods of recognition—were deeply heartfelt. The promotional video went viral, resonating with audiences far beyond the village.

Soon after, the production team invited the grandmothers to paint scenes inspired by the drama and to exhibit their works at the “When Life Gives You Tangerines Geumeundong Village Festival,” an event in Seoul that Netflix organized to celebrate the drama’s successful run. Eight grandmothers made the journey to Seoul, joined on their trip by an art teacher, a few friends, and 30 young villagers. Three of the grandmothers needed wheelchairs. IU, who attended the event, was visibly moved by the exhibition, and she warmly embraced each of the grandmothers.

While in Seoul, the group stayed at a hotel right next to the Haja Center, and Haja students who had once visited Seonheul to paint with the grandmothers remembered the bond. The students prepared a breakfast full of care: rolled omelets, soybean paste soup, octopus jeotgal (salty preserved seafood), and rice cakes. There was even a charming little mishap—the rice did not cook in time because someone forgot to start the rice cookier!

Since then, the grandmothers have become unofficial ambassadors for the drama. The popular Jeju YouTube channel Mworaeng hamaen (which translates into “what are you talking about?”) visited the grandmothers to watch the drama together, and many videos featuring the grandmothers now circulate widely on YouTube and Instagram. We’re now preparing for another exhibition this May.

In a serendipitous twist, Pisa, a Haja alum who currently works in cultural planning in Dubai, happened to visit Seonheul and saw the grandmothers’ artwork. Inspired by what she saw, Pisa proposed organizing an exhibition in Dubai to celebrate the 45th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between South Korea and United Arab Emirates.

All of this reminds me of how long connections can last and how intimately the local and the global are now intertwined.

It’s moving to see how popular culture can create new ties between people. This reminds me also of the young women collectively waving K-pop light sticks at the recent impeachment rallies against Yoon Suk Yeol. What do you make of this phenomenon?

What’s unfolding there feels like the civic expression of a sensibility long cultivated through fan culture. I was moved by the story about how those who could not attend the rallies in person sent warm coffee and kimbap to protestors—a gesture rooted in fan community practices. Though the generation now in their 20s and 30s has been shaped by neoliberal individualism, fan culture has nurtured its own ecology of care. One fan’s words stayed with me: “I came out to the streets because I couldn’t let my beloved singer live in a country like this.” That kind of loyalty transcends entertainment and takes on a political significance. In turn, celebrities like IU, Girls’ Generation, and NewJeans prepared food, drinks, and hot packs for fans who attended the protests, where Girls’ Generation’s debut song “Into the New World” was also sung as a protest anthem.

In the world of fandom, there’s a longstanding tradition of fans offering extravagant gifts to idols (jogong, meaning “tribute”) and idols responding with their own gestures of gratitude (yeokjogong, meaning “reverse tribute”). What’s striking is how this ethos of mutual care has expanded into the civic space, becoming a new form of protest culture. It’s no longer just about personal survival. Fans and stars alike are building a world of devotional care. The word “추앙,” which Yeom Mi-jeong in My Liberation Notes uses when she asks Mr. Gu to “revere” her, comes to my mind—the Sino-Korean word suggests an intense admiration and unconditional support. In a time of apathy and disconnection, I believe such devotion and admiration carries profound meaning. I want to explore the civilizational depth of admiration itself. I am also curious about why the majority of fans are women.

Any last thoughts you’d like to share with us?

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Haja Center, and we’re planning a kind of homecoming—a gathering of old friends, collaborators, and dreamers. Haja alumni are now scattered across many fields, riding the momentum of the Hallyu wave. Some are living fast-paced, successful lives, while others are still searching or perhaps rebuilding after early achievements. But regardless of where they are, the spirit of Haja remains the same. Haja has never been about building a utopian movement; it is fiercely independent in spirit. We want people to learn how to reclaim and re-enchant their own lives.

Over the past 25 years, the youths who have come to the Haja Center have changed. The wave of neoliberalism in the 2010s led to a survival generation—teenagers whose attitudes differed significantly from that of the previous generation. These teenagers didn’t come to Haja seeking to do something new; rather, they came because they rejected a society in which survival meant harming others.

As we entered the 2020s, even those youths became fewer. Instead of teenagers, it is now university students who come, saying that they are here not to search for answers but because Haja felt like a safe space. These students have launched the third stage of the Haja Center, one grounded in growth and care. At a time when individual survival has become paramount, these students want to stay in this safe place for a while, sharing information and resting with other people who will not harm them. We are in an era that needs spaces like these—Adventurers’ Guilds where people can meet others and gather what they need before setting out on their adventures.

Watching the evolution of the Haja Center, I hope that Hallyu fan communities can also create adventurers’ guilds where fans who care for and dedicate themselves to each other can gather and start activities to save the world. Ə

For readers who want to learn more about the history of Hallyu, Professor Cho recommends Jun-man Kang’s History of Korean Wave: From the Kim Sisters to BTS | Why Are People Crazy About BTS and Parasite? (2020) and Seok-kyung Hong’s BTS On the Road (2023).

Note: For consistency, Korean names that may be familiar to readers from English-language publications are rendered with the given name first and the family name last. All other names follow Korean convention, with the family name coming first.