“The Cold War Ended, and Orion’s Choco Pie Won”

In 2014, Korean American artist Mina Cheon covered the basement floor of the Ethan Cohen Fine Arts Gallery in New York City with 10,000 choco pies. One of South Korea’s most recognizable alimentary exports, the choco pie brands itself as a uniquely Korean snack. Its red gold packaging features the hanja for “jeong,” which the South Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism defines as “a unique element of Korean culture” denoting “a warm feeling of love, sympathy, and attachment between people.” In advertising the choco pie, the manufacturer Orion Corporation capitalizes on the cultural association between its trademark product and mandatory military service in South Korea, during which choco pies are often distributed to soldiers as sugary reprieve. That is to say, the choco pie circulates in South Korea as a constitutive element of social relations.

A 2007 Orion advertisement uses a tender interaction between a mother and her son to to link the choco pie to the idea of jeong.

Within the Korean diaspora, memoirs like Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H Mart (2021) and Grace M. Cho’s Tastes Like War (2022) also center food’s role in mediating kinship ties. Zauner’s reflections on her mother’s recipes and Cho’s discussion of postwar Korean tastes for powdered milk and budae jjigae (army base stew) point to how subjective experiences like taste in fact sustain intergenerational and collective memory. The title of Cho’s memoir comes from her mother’s refusal of powdered milk—a commodity first imported into South Korea through the US military—due to its “[tasting] like war.” Tracing the origins of popular dishes back to the outbreak of the Korean War and the US military occupation of Korea, Cho reframes the connective potential of food as not inherently nourishing but rather unsettling, even traumatic. As numerous studies have shown, the making and consumption of food has always been entangled with power—from the commercialization of sugar, tea, and pineapples in Europe and the so-called “New World,” which depended on enslaved and indentured labor, to the ingestion of “Jim Crow cookies,” opium, and sushi, which at once enforce and trouble racialized distinctions between the eater and the eaten.

Choco pies and their transnational circulation are no exception. Despite the pie’s branding as a quintessentially South Korean product, its story is a transnational one with roots in the US South. In 1973, Kim Yong-chan, an executive from Tonyang Confectionary (present day Orion), tasted a moon pie during his visit to the US state of Georgia. After returning to Korea, Kim and his colleagues experimented with different baking techniques to create their own domestic version. One year later, the choco pie was launched. In 1993, after Russian sailors in Busan reported an affinity for the snack, Orion began exporting choco pies to Russia and would go on to open factories in Russia and Siberia. Today, factories operated by Orion and its subsidiaries, as well as by LOTTE Wellfood, a Korean food company that manufactures its own choco pie, can also be found in India, China, and Vietnam, where the snack also comes in well-loved local flavors like watermelon and black sugar milk tea.

While its popularity continues to grow abroad, the choco pie has also become a crucial ingredient for inter-Korean relations. In 2014, anti-Pyongyang “balloon activists” in South Korea launched giant helium balloons stuffed with thousands of choco pies over the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) in hopes that the snacks would advertise the sweet trappings of Southern democracy. At the same time, reports of the pies being sold in the North at inflated prices circulated far and wide in the press. South Korean companies had begun distributing the pies as wage supplements to North Korean factory workers employed at the since-shuttered Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC), and the workers would bring the pies back with them to the North.

Located in a special North Korean administrative district near the border of the DMZ, the KIC had opened in December 2004 as a joint economic endeavor between the two Koreas. Mainstream media and politicians celebrated the occasion as a significant turning point for North-South relations and one that heralded opportunities for further inter-Korean cooperation. In 2016, however, aspirations waned after then-South Korean president Park Geun-hye (since impeached) shuttered the KIC, citing North Korea’s satellite launch that same year as a reason. In 2020, North Korea detonated the Inter-Korean Liaison Office in Kaesong, revealing the degree to which relations had frayed particularly with the ramping up of Southern right-wing warmongering.

As a metonym for the KIC, the border-crossing choco pie is a symptom of Korea’s division that registers what might be at stake for various geopolitical actors who are dedicated to maintaining or contesting that division. The choco pie’s mobility has made the snack a highly visible commodity, permitted to cross the DMZ while Korean people have been repeatedly prohibited from reuniting with separated family members and from visiting their hometowns in the North. Media commentators and jingoist politicians in the United States and South Korea have clamored to comment on the circulating snack, eager to make claims about the so-called “Hermit Kingdom” to serve their own agendas.

But for diasporic Korean artists like Cheon and Jin Joo Chae, the pie’s nostalgic familiarity and branding power opens up the space for reconsidering fundamental questions of division and reunification. How does the confection’s sugary taste and symbolic power relate to its role as constitutive matter of foreign relations? How might the choco pie be understood not as a merely edible commodity but as a method for charting the ongoing legacies of the “cold war” in Asia? How do circulations of the pie become the grounds for reimagining political possibility not only between the divided Koreas but also within a world that remains implicated in the ongoing Korean War?

Eating Toward Peace? On Consumption and Cold War Aesthetics

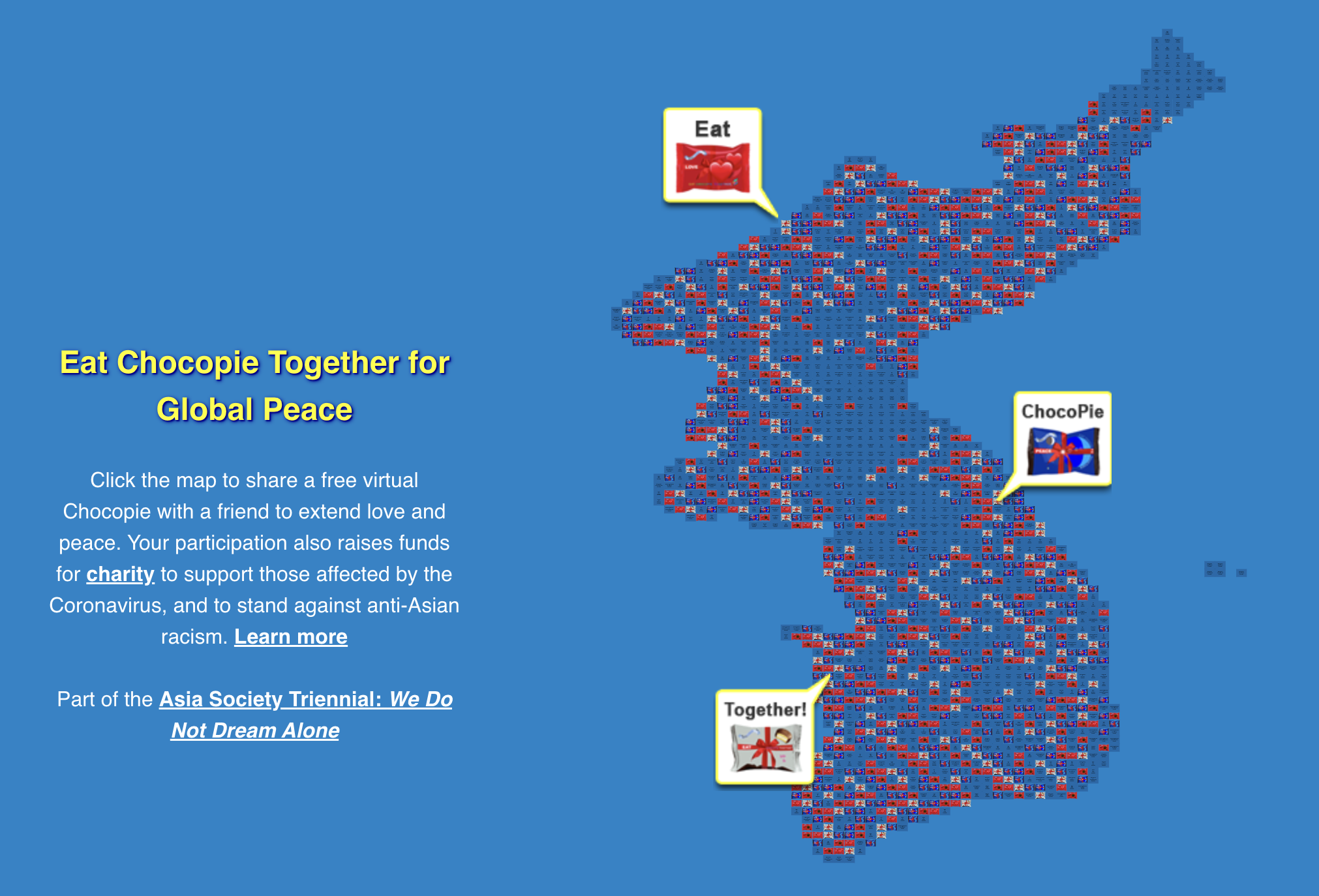

Titled “Eat Chocopie Together,” Cheon’s art installation takes up the choco pie as “the cultural symbol of inter-Korean unification efforts, from the Koreas to the world.” Former South Korean president Moon Jae-in and first lady Kim Jung-sook visited Cheon’s installation when it was subsequently presented at the 2018 Busan Biennale, in the same year that Moon and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un participated in a historic inter-Korean summit.

“Eat Chocopie Together” invites visitors to take and taste pies directly from the installation, an act Cheon likens to “taking a bite for peace.” Cheon’s framing transforms the visitor into a participant who consumes not only the choco pie but also what the pie purportedly represents: the possibility of a “peace” that heals the scars of division. Though rooted in the context of the Korean War, Cheon’s invocation of terms like “peace,” “love,” and “kindness” in relation to “Eat Chocopie Together” are vague, and perhaps intentionally so. Suggestively, a digital version of the work, which allowed participants to mail a virtual choco pie to loved ones, launched during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Derived from the specific context of Korean reunification, “love and peace” morphed into an abstract motif for gathering virtually in the face of social distancing. While “Eat Chocopie Together” exemplifies Cheon’s interest in the undeniable inseparability of politics and culture—“because these are the two things people are surrounded by in our daily lives”—the consequences of abstracting the choco pie away from the context of inter-Korean reunification warrant further investigation.

Sponsored by Orion, “Eat Chocopie Together” began as a part of Cheon’s 2014 solo New York exhibition Choco·Pie Propaganda: From North Korea with Love. The exhibition featured paintings that combined the socialist realism of state-sponsored North Korean art with abstract expressionism and pop art, both of which belong to the American postwar art tradition. Cheon refers to her distinctive aesthetic as “polipop,” through which she aims to “make art that’s more accessible to the audience and to the public.” She explains: “I try to make [the art] look, on first appearance, fun, possibly provocative, but more eye-catching and sweet as a way of entry” into the subject of Korea’s division.

While Cheon has noted that she is not the first to make polipop, she seldom explicitly invokes the Chinese “political pop” art movement from which the term originated. As the Revolutions of 1989 led to the collapse of the Soviet Union and produced reverberations in post-Tiananmen China and the Global South, Chinese artists like Wang Guangyi, Yu Youhan, and Li Shan fused socialist realist iconography with the visual grammar of global American and European brands in order to capture the ideological tensions that shaped contemporary life in the People’s Republic. Meanwhile, in South Korea, successive anti-communist military dictatorships under the sway of US neocolonial power increasingly cemented South Korea’s place within the global capitalist orbit, even as these dictatorships clashed with the popular struggle for democracy. For many Korean students who led the democracy protests in the 1980s, the meaning of “democracy” was marked by the deferred dream of reunification. These students also saw the United States as a key obstacle to this goal because of its support for dictators like Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan.

As an artist based between the United States and South Korea, Cheon has spoken about how Korea’s division has shaped her own experience. Split along the 38th parallel by the Soviet Union and US military planners after two US colonels drew the line at the close of World War II by consulting a National Geographic map, Korea found itself “liberated” from Japanese colonialism in 1945 only to be immediately reoccupied by the US military government. Three years after the United States intervened in the Korean War, the armistice of July 1953 permanently established the Demilitarized Zone that, despite its name, remains among the most militarized borders in the world. In 2004, Cheon visited the Mount Kumgang Tourist Region in North Korea, which had been established two years prior to facilitate international tourism particularly by visitors from South Korea. The trip inspired Cheon’s creation of “Kim Il Soon,” her North Korean alter ego who would not only share attribution for Cheon’s work, but who would also appear across a number of her paintings. Cheon describes her alter ego as “a cosmopolitan North Korean who knows how to paint abstraction in her dreams.” Her name and iconic status an echo of Kim Il Sung, Kim Il Soon is a woman who wears many hats: a nationally recognized DPRK artist, a naval commander, a farmer, a scholar, and the “mother of unification.”

In 2017, Cheon adopted the persona of Professor Kim (Il Soon) in recording a series of performance-lectures on contemporary art, which she then copied to hundreds of USB drives. With the assistance of anonymous Korean supporters, Cheon transported these USB sticks in helium balloons over the DMZ. Information transmission across borders both figurative and territorial is a theme that runs throughout Cheon’s oeuvre, whether it be sending virtual choco pies in a time of social distancing or flying media art into the North. The portability of aesthetics, thematized in Cheon’s polipop works, finds material mobility in her artistic transmissions. Art’s ability to move also makes it a ripe field for imagining renewed political possibility, a sentiment that Cheon articulates in her characterization of Kim Il Soon as “an alternative form for all the political dealings and mishaps that are confounded by the father ‘dear leaders’ of the world, the massive culture of hatred and war of words and missiles that are threatening peace on earth.” But if Kim Il Soon is meant to present a feminist alternative to the chauvinistic domain of diplomatic backrooms, she also risks over-representing the terms of an imagined “peace” between the Koreas, one that attempts to bring people and nations together despite, rather than through, their differences.

Cheon’s aesthetic approach diverges from that of her Chinese political pop predecessors: polipop’s explicitly gustatory twist seems less a comment on tensions between socialist and capitalist modes of production than a reach for palatability. Cheon frequently draws attention to this by underscoring the phonetic resonance of “polipop” with “lollipop.” There may be something to be said for the strategic value of palatability when the Korean War continues to be referred to in the United States as a “forgotten war” due to the lack of public education and awareness about the war (a bitter irony compounded by the fact that the Korean War remains ongoing). Yet if food’s entanglement with power is to be taken seriously, the mobility represented by acts of consuming together, whether food or art, must not be fetishized as inherently capable of facilitating “peace.” Instead, it is necessary to interrogate the historical and material conditions under which Korean people and goods have been subjected to uneven experiences of mobility and immobility. Why has the choco pie been permitted to move across the DMZ when Korean people themselves have not?

From Tongil to Gyeonghyeop: The Changing Politics of Reunification

Tongil, or reunification in Korean, has long invoked both the theft of sovereignty, concretized in the external imposition of the DMZ, and the possible restoration of broken geographical and kinship ties. However, South Korean mainstream attitudes toward reunification have undergone significant shifts in the past several decades. In 1972, the Northern and Southern governments came together to draft the North-South Joint Communiqué, a groundbreaking document that outlined conditions for reunification. The first and foremost condition stated that unification was to be “achieved through independent Korean efforts without being subject to the external imposition of interference.” Over the next two decades, however, the possibility of reunification would become more challenging to imagine as the divided Koreas traveled down differentiated paths: one, toward the collapse of life and industrial labor under the flag of state socialism; and the other, toward entry into the global “free market,” fueled by worker subjection to export-led industrialization and the privileging of private firms under successive military dictatorships.

The prospect of establishing reconciliation would not be revisited by both Koreas until 1991, when North and South signed the Agreement on Reconciliation, Non-Aggression, and Exchanges and Cooperation between South and North Korea. In a crucial departure from the earlier conceptions of reunification—such as the uniting of territory under a shared government—the Agreement on Reconciliation established that the two Koreas would respect each other’s internal political systems and cooperate to promote mutual interests in the global arena. Subsequent Democratic presidents in South Korea have largely favored economic cooperation (or gyeonghyeop) over political reunification. The opening of the KIC under Democratic president Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy reflected this trend, heralding the mitigation of geopolitical tensions and the possibility for restored fraternal goodwill.

During its intermittent operations from 2004 to 2016, the much celebrated complex hosted as many as 125 South Korean companies that collectively employed nearly 55,000 North Korean workers, all of whom received wages paid in US dollars. For the North, the KIC purportedly offered a means for economic recuperation and currency inflow, as wages were paid to the North Korean government. The North Korean government reportedly paid a majority share of these wages back directly to workers, in kind as goods and vouchers, and about five percent as North Korean won. The government then reportedly redistributed the remaining 30 percent taken by the government to the Kaesong City People’s Committee, which used the funds to establish social services for workers. For the South, which offered financial incentives to local firms that participated in the KIC, the venture allowed local companies to source materials from South Korean suppliers rather than going overseas in search of cheaper supply costs. As worker incentives, KIC companies would routinely distribute South Korean choco pies up to several times a day to their North Korean employees. According to US and South Korean media, these employees would then bring the pies back to the North either to sell or to trade in exchange for other goods, such as other food items.

As one of the few venues for sanctioned contact between North and South Koreans, the KIC seemed an index of the state of North-South relations. The choco pie incentives prompted much commentary proclaiming North Korea’s “susceptibility to outside influence in a society commonly regarded as impenetrable.” Spectators claimed the pie’s capability to align the Koreas, specifically through the subsumption of difference. In a 2018 TED Talk, Cheon explains that the New York debut of “Eat Chocopie Together” allowed “an American audience to taste the sweet desire of North Koreans. . . . By tasting choco pie, they are able to concentrate on how North Koreans also have desire and love. In a way, it’s humanizing North Koreans when the rest of the world’s impression [of North Koreans is that they are] backwards and animal-like.”

While Cheon aims to challenge US tendencies to villainize North Korea, the humanism of “Eat Chocopie Together” relies upon an apparent proof of commonality—one located in a shared hankering for mass-produced sweets—and thereby largely elides the specificity of the very terms of humanization that it takes up. Who gets to determine the criteria by which entire populations are deemed human and non-human, and why? And what might it look like to refuse that criteria—to confront the fact that the very terms of valuation that we have been given are themselves political?

Choco Pie Orientalism: Deconstructing Humanitarianism and the Human

Upon entering the Korean War, the United States waged a carpet bombing campaign against the North, dropping 32,000 tons of napalm that destroyed an estimated 75 percent of Pyongyang and killed nearly one-fourth of North Korea’s population, facilitating the eradication of entire families and villages. “We could not stand idly by and allow the communist imperialists to assume that they were free to go into Korea or elsewhere,” Truman wrote in his 1956 memoirs. Since the Korean War began, the West, led by the United States, has continued to dehumanize North Korea as a key node in a global “axis of evil,” as former US president George W. Bush put it. US military intelligence conceives of North Korea as a “black hole,” citing the West’s limited access to the North Korean regime and its media. US politicians continue to cast the country as a justifiable military target, with President Donald Trump having allegedly mused about deploying a nuclear weapon against North Korea. To call up Edward Said’s formulation of orientalism, the “Orient” is not an objective geography or culture with fixed characteristics but a reflection of the West’s perception of the so-called “East,” a perception that the West wields to justify its global domination. That is, the United States’ pointing its diplomatic finger-cum-trigger at North Korea is less an indicator of the North’s “irrationality” than it is a reflection of US imperialism. The US penchant for anti-communist war is simply one manifestation of its virulent racism.

From Korea to Hawaiʻi, Vietnam, and Palestine, US imperial violence has historically depended on the construction of a racialized enemy “other”—an “other” who is deemed incapable of rationality, civility, and self-possession, and therefore in need of either humanitarian rescue or nuclear annihilation. At stake here is not merely the accuracy of such constructions but the assumptions about humanity that underpin them. Jamaican writer and critic Sylvia Wynter points out that these assumptions, which determine “our present ethnoclass mode of being human,” in fact misrepresent the condition “of the Western and westernized (or conversely) global middle classes” as “that of the human species as a whole.” For Wynter, the very notion of a universal human subject is in itself a colonial one—one used by the white, male, European Enlightenment subject not only to justify physical conquest but also to colonize and define what it means to be human, whether it be through the formation of academic fields beholden to European canons, the selective enforcement of international human rights, or the creation of a global financial system that perpetuates neocolonial hierarchies through the imposition of debt on the Global South.

Likewise, attempts to humanize North Korea on the basis of a taste or desire for choco pies are contingent on the North’s capitulation to capitalism. This conditional finds expression in diasporic Korean artist Jin Joo Chae’s exhibition The Choco Pie-ization of North Korea, which opened at the now-closed Julie Meneret Contemporary Art gallery in the same year as Cheon’s New York exhibition debut. Subtitled “the sweet taste of Capitalism with Communist cream,” Chae’s exhibition begins with introductory wall text that includes a quote attributed to Lew Rockwell, self-professed “anarcho-capitalist” and founder of the right-wing think tank Mises Institute. The quote reads: “The North Korean regime . . . is in danger. Not from military attack, but from capitalist subversion. . . . Capitalist ideas and goods, from South Korea and China especially, are slowly subverting Marxism-Leninism.” Likening the choco pie’s entrance into the North to a military victory, wherein the last Asiatic domino falls under the lure of free market ideology, Rockwell’s remarks echo modernization theory, a cold war framework that maps societies onto a linear evolutionary path and establishes liberal capitalist democracy as the modern destination toward which much of the Global South is headed but at which they have not yet arrived. (Consider how South Korea is narrated as a paragon of economic success, a story that begins with postwar poverty and culminates with South Korea’s entry into the OECD as its first and only member to have been a former aid recipient.)

Jin Joo Chae discusses her exhibition The Choco Pie-ization of North Korea with The Korea Society.

Such condescending fantasies of North Korea’s inevitable capitulation to capitalism find ironic expression in one of Chae’s sculptures. The sculpture features a sack of rice covered in dollar bills sitting atop a stack of shipping boxes, each of which is filled with choco pies. On the wall behind, a red LED sign displays the snack’s day price (“$1.72”) as if it were relaying stock prices or betting odds. The sides of the sculpture are smeared with what appears to be chocolate and stenciled with the word “DESIRE,” while the boxes rest atop a bed of rice grains, crushing them beneath their weight. By juxtaposing the choco pie, a processed snack food, with rice, a staple crop, the sculpture invites viewers to consider the politics that shape access to means of subsistence. Despite reports of declining crop yields in North Korea as a result of flooding and drought, rice exports to North Korea have been strictly regulated under the DPRK Sanctions Regime imposed by the UN Security Council. In this regard, the flow of choco pies from the South to the North evidences not so much North Korean “humanity” as it does the shallow humanitarianism of US liberal democratic governance, which operates as a sugary veneer for the continued subjugation of North Korean people.

The unequal terms of the KIC, under which factories built by South Korean corporations are staffed by North Korean labor, might be understood as another expression of this imperial dynamic. What falls under the umbrella of “economic cooperation” in fact perpetuates Northern dependency on the South. According to a blog post about Chae’s exhibition, visitors could purchase a choco pie to eat if they added their own dollar bill to the sculpture. If “freedom” in postwar South Korea is synonymous with the ability to enjoy consumer goods, the “sweet taste of capitalism” comes at a price, particularly for North Koreans.

In November 2017, three years after Cheon and Chae’s exhibits opened in New York, a 24-year-old North Korean soldier, Oh Chung-sung, crashed his car in the DMZ and emerged from the wreck, suffering a battery of gunfire while sprinting through the border zone before being dragged across the Southern Limit Line by South Korean soldiers. Oh, who sustained five different bullet wounds, had to be airlifted to a hospital for treatment. US and South Korean media were delighted to report that, when he finally regained consciousness days after his surgery, Oh allegedly asked if he could have a choco pie. Orion promptly sent 100 boxes of pies to Oh’s hospital room, though Oh was unable to eat them when they arrived. His body, it was reported, had not yet recovered from the injury and subsequent treatment, rendering him incapable of digesting the snack even if he wished.

Choco Pie Circuits: From Modernization Theory to Divergent Modernities

As with Cheon, Chae reappropriates the iconography of mass consumer goods. But unlike “Eat Chocopie Together,” Chae’s exhibition does not uncritically imagine the choco pie as a (re)unification medium that draws visitors into closer proximity to North Korea and to each other. Instead, the choco pies in Chae’s work produce not so much a sense of connection as disorientation, alienation, and even repulsion. The Choco Pie-ization of North Korea features oversized images of choco pies that spell out the snack’s name but in the Coca-Cola logotype. Upon closer look, it turns out that the choco pie images, made with dark, semisweet, and milk chocolate ink, have been printed on sheets of Rodong Sinmun, North Korea’s official party organ. One sculpture features a tipped cardboard box, from which liquid chocolate and choco pies splatter onto the gallery floor. In another, a golden choco pie placed with cutlery sits inside a glass box, too precious to consume. These different iterations of the choco pie present the commodity image as a floating signifier and a screen upon which the West projects its fantasies of North Korea, whether it be ethnocentric affirmations of North Korean “humanity” or the imminent breakdown of the North Korean regime.

The overdetermined signification of the choco pie mirrors the way “North Korea” tends to function as ideological shorthand for a whole host of political imaginaries, particularly anxieties perpetuated by the “capitalist West”/“communist East” cold war binary. Chae wryly revises her citation of Rockwell in the exhibition’s subtitle, “the sweet taste of capitalism with communist cream,” and in the contrastive titles of two choco pie prints from her Coca-Cola logotype series. The titles repeat with a crucial difference: “The Sweet Taste of Capitalist Cream” in one becomes “The Sweet Taste of Communist Cream” in the other. Replacing “Capitalist” with the alliterative “Communist,” Chae links two terms typically thought of as antithetical and as indexed to opposing geographies, histories, and modes of production. As a result, she pushes viewers to consider how they might function as mirrors of one another. Are the prints a commentary on the sweet seductions of American consumerism or the centralized operations of North Korean state media? Rather than occupying either side of this critique, the choco pie yokes the two sides together, exposing their ideological work. In each case, “capitalism” or “communism” functions as a reductive signifier for entire geographies and groups of people. Within a world structured by US imperialism, though, they are signifiers accompanied by radically different levels and kinds of risk.

In a world structured by global capitalism, “communism,” rendered as capitalism’s antithesis, operates as a designation that renders entire groups vulnerable to various forms of state-sponsored violence sanctioned under liberal democracy and enforced by US military violence. During Yoon Suk Yeol’s attempted autocoup in South Korea in December 2024, the since-disgraced former president attempted to scapegoat “pro-North, anti-state” forces for his actions. In this light, it becomes crucial to expose the relentless vilification of the North as a longstanding tactic in South Korea’s right-wing playbook. In March 2025, live-fire military drills conducted as part of annual US-ROK war games (ironically named “Freedom Shield”), which simulate a North Korean nuclear attack, drew public outcry when two fighter jets accidentally injured at least 29 people after dropping eight MK-82 bombs on the city of Pocheon. Among the civilians injured, six were reported to be migrant workers.

As the rabid anti-communism of the Trump administration and the rise of right-wing forces across the world threaten to ignite a “new cold war,” critical commentators have pointed out that “old Cold War” power plays and rhetoric now resurface under material conditions that differ dramatically from the immediate post-World War II moment. In the present-day context of rapid globalization and China’s expanding economic reach, cold war dichotomies like capitalism/communism, East/West, and democracy/authoritarianism fail to articulate the economic phenomena and social forces that structure the state of the contemporary world. As segments of the US left take up China and its allies as a concrete alternative to US imperialism, contestations over the possibilities and failures of “actually existing socialism” have also unfolded both domestically and globally. In the context of these debates, “capitalism” and “communism” must not serve as reductive ideological signifiers. Rather, we might use them as productive anchors for working through their attendant contradictions, for attending to the specificity of contemporary global conditions, and for imagining genuinely different political possibilities.

While the “old Cold War” is one inheritance that the global left is tasked to grapple with, movements for decolonization that rocked the Third World are another. In her account of the North Korean Revolution of 1945-1950, Suzy Kim situates the North Korean Revolution within the history of global modernity. Critical of the impulse to treat North Korea as an exception that is out of joint with the rest of the world, Kim suggests that attending to the formation of North Korea might reveal more universal, and therefore “inconvenient,” truths about the contradictions of modern life everywhere. As Kim points out, “[t]here is enough responsibility to go around, including that of the United States, for modernity’s discontents.” Kim also declines demands to assess whether “variants of ‘actually existing socialism’ are genuinely socialist.” Instead, she frames her account of North Korea’s “socialist modernity” as an effort to trace what it looked like and meant for everyday North Koreans to “[put] what they considered to be socialism into practice through mass participation” as a response to “colonial” and “capitalist” modernity. If there is a theory of modernity to be had, Kim wagers, a key tenet is its belief in the capacity of humanity to effect change.

Whether the choco pie can offer a way through these contradictions remains uncertain. There is the KIC, which remains closed today—a closure further cemented by the previous Yoon administration’s 2024 disbanding of the South Korean foundation responsible for managing Kaesong-related operations. There are the choco pies that the South Korean military distributes to men doing their mandatory military service at the DMZ, and there are those that float over the Demilitarized Zone. There is Cheon in New York in 2013, dressed in a North Korean military uniform, exiting a cab and making her debut as Kim Il Soon. There is the unforgettable 2013 clip of Richard Horne, a US soldier stationed in Korea, speaking at the annual ROK Army Support Group Korean-language speaking contest. Recalling his Korean colleague Choi—a member of the Korean Augmentation to the United States Army (KATUSA)—whenever he sees the snack, an impassioned Horne asks the audience if they have ever eaten a tear-soaked choco pie. There is Horne’s pause, for laughter.

There is a longer pause that surrounds the joke, the speech, the uniform—the pause of permanent military occupation as a form of ceasefire. There is also another kind of laughter, shared between separated Korean families reuniting near the end of their lives. There are the choco pies that change hands between their children, who meet for the very first time while carrying bags stuffed with gifts like pajamas, vitamins, and undergarments for the winter. And then there is Oh Chung-sung, whose defection journey illustrates the consequences of division in their most immediate, corporeal form. There are modernity’s discontents, and dreams of a different world, and there is us, their inheritors. From the revolutionary experiments of the past to the global uprisings of the present, what might the everyday choices we make—down to what and how we eat—yield by way of freedom dreams? Ə

Note: The title of this essay—“The Cold War Ended, and Orion’s Choco Pie Won”—comes from the headline of a Korea JoongAng Daily article published in 2019.