To Where the Flowers Are Blooming: Gwangju’s Literary and Material Memoirs

What does it mean to walk slowly? Perhaps this is the posture one ought to adopt in moving through the 5.18 Archives: walking slowly, wandering while pondering deeply, and lingering quietly in an exhibition space engraved with the past. I reminded myself to tread gently as I walked over the thick glass floor, under which abandoned shoes lay scattered next to rusty bullets on asphalt. Their silent presence urged reflection with my every step. Under the stark exhibition hall lighting, the shadows cast by these ownerless shoes became etched into my memory as vivid, tangible remnants of a devastating reality.

Housed in the former Gwangju Catholic Center on Geumnam-ro, a historic site of what is now officially known as the May 18 Democratization Movement, the 5.18 Archives preserves artifacts from the Gwangju Uprising in commemoration of the Korean people’s struggle for democracy. In December 1979, the military dictator Chun Doo-hwan had seized power in a coup d’état and then quickly declared martial law to cement his rule. When the students and citizens of Gwangju took to the streets in protest, Chun sent in the military to violently suppress the protests, leading to mass civilian casualties. Those lost shoes sealed under glass in the archives brought back the chaos that erupted on Geumnam-ro in May 1980, when armed soldiers began slaughtering ordinary citizens.

The day was February 4, 2020, and as fieldwork for my doctoral research, I had come to the 5.18 Archives in search of those materials now inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. The scenes I encountered there challenged my initial expectations. The May 18 Democratization Movement was not a bygone event confined to the pages of a history textbook. The story of Gwangju was still alive, a present and ongoing narrative speaking through the battered shoes on display. I learned from the exhibition guide that these were not the actual shoes worn by protestors, but rather props designed to re-enact the historical moment. Somehow, that gave them even greater pathos, their very materiality invoking not only the shoes that once protected someone’s feet but also the lives that never returned to them. Taking on the crumpled shapes of those lost shoes, they seemed to solicit the visitor, as if to ask: Who, now, will step into the stories they embody? Who will carry forward the paths once trodden?

In April 2021, more than a year after that first visit to the 5.18 Archives, I moved to Gwangju and began my five-month internship program at The May 18 Foundation. I knew I needed to immerse myself in Gwangju culture to better understand the meaning of that historic event. Having never experienced the month of May in Gwangju, I thought working at the foundation during this period might also provide new insights for my doctoral thesis, which looked at cinematic depictions of the Gwangju Uprising to explore the relationship between film, memory, and counter-histories.

During my internship, I had the chance to speak to a director specializing in independent film and documentary. I asked the director a few questions about her work on Gwangju, but she saw me as a relatively young outsider who lacked the necessary experience and background. She advised me that it would take a great deal of time and effort to truly grasp the pain endured by the people of Gwangju. It was then that I realized the inadequacy of my purely rationalist perspective. As I met and interacted with more Gwangju citizens, I began to understand, even if only slightly, the loneliness and isolation they felt in the aftermath of the Democratization Movement.

My experience at The May 18 Foundation marked the beginning of my true engagement with Gwangju—not just as a responsible researcher, but also as a human being practicing solidarity and empathy and as a memory mediator who could help pass down these stories to future generations. I began to realize that even for well-known historical events recognized by the state, official documentation only scratches the surface of the truths that exist.

Ironically, Gwangju experiences its deepest mourning during the season when the flowers bloom. Had I not visited Gwangju, I might have never known this. While the other parts of the country celebrate with spring festivals, Gwangju revisits the past, honoring the memories of those it has lost. Every year on May 17, the city honors the spirit of the May 18 Democratization Movement through the 5.18 Democratic Eve Festival on Geumnam-ro in downtown Gwangju. The official commemoration ceremony on May 18 itself takes place at the May 18th National Cemetery located on the northern edge of the city, from which visitors can then proceed sequentially to other key historical sites by walking along the May Road (a a themed series of 18 walking tours) or by taking the Gwangju bus route 518. One such historical site is Jeonil Building 245, the old Jeonil Broadcasting Corporation address whose walls bear 245 bullet holes from gunshots fired from a military helicopter. Gwangju’s commemoration extends beyond the day itself and continues on a daily basis, as visitors can take bus 518 or walk along the May Road on any day of the year.

Surprisingly, I had never walked along Geumnam-ro prior to my visit to the 5.18 Archives. I had not tried to imagine what it would have been like to be in the shoes of those nameless individuals who had gathered at the fountain, who had read declarations and recited poems, and who were eventually killed on this road. Though I was not present in Gwangju in May 1980, the abandoned shoes materialized in the Archives began to haunt me, like the throng of memories from that day. Their footprints seemed to follow me wherever I went in Gwangju. It was as if they carried their past into my present. And I began to reflect anew.

Shoes have always been poignant memory objects for Gwangju. They appear as powerful symbols in various cinematic depictions of the Uprising, including the movie A Taxi Driver (2017) and the K-drama Youth of May (2021). Based on a real story, A Taxi Driver follows Kim Man-seob, a Seoul taxi driver who inadvertently took the German journalist Jürgen Hinzpeter into Gwangju during the Uprising, at a time when the city was under siege and communication with the outside world had been cut off. Worried about his daughter and reluctant to get caught up in the conflict, Man-seob leaves Gwangju without Hinzpeter after witnessing the state’s violent actions.

On his way out of the city, a ground-level wide shot confronts the film’s audience with numerous ownerless shoes scattered on the desolate Gwangju streets. Man-seob’s taxi, initially out of focus in the background, is slowly approaching the shoes. The audience is not sure if Man-seob has seen or even cares about those shoes until he makes a pit stop in neighboring Suncheon, where a market stall selling shoes catches his attention. On screen, these shoes hang from the stall’s makeshift ceiling and frame Man-seob from above, in direct opposition to the Gwangju shoes he had previously driven past (and perhaps over). And when Man-seob picks out a pair of pink shoes for his daughter, he lifts them upward, from below—as if rescuing the abandoned shoes that he had once overlooked.

Moved by what he sees, Man-seob makes the life-altering decision to return to Gwangju. Back there, he finds Jae-sik, the student protestor whom he had befriended earlier, dead in the hospital, with one foot missing a shoe and a sock. Jae-sik’s bloodied and scratched-up foot bears the marks of violence, but when Man-seob replaces Jae-sik’s missing shoe, it also testifies to Man-seob’s emerging solidarity with the people of Gwangju. In an interview, the director Jang Hoon explains that the shoe motif in A Taxi Driver drew inspiration from archival photographs of the Gwangju Uprising, many of which depicted only shoes scattered on streets that were otherwise emptied of signs of human life. As Jang notes, “the act of Man-seob putting the shoe on Jae-sik’s foot is, at the very least, a small gesture of comfort.” In the film, Man-seob eventually drives Hinzpeter out of Gwangju so that the journalist can broadcast his recorded footage, alerting the world to the truth of Gwangju.

Similarly, Youth of May uses shoes to illustrate the heartbreak of losing a loved one to state brutality. They embody the love of a father when he buys new shoes for his children, Myung-hee and Myung-soo. Myung-hee tightly laces her younger brother Myung-soo’s sneakers for him to encourage him in his race, but when she stumbles upon a similar sneaker left behind on the ravaged streets after the military has begun its violent suppression, she realizes her brother might be in danger.

In both A Taxi Driver and Youth of May, shoes testify to one’s heartfelt wish for the wellbeing of loved ones; the gift of shoes expresses the hope that they will be guided along a good and safe path. But when such hopes are brutally trampled upon by state violence, a single abandoned shoe becomes a powerful metonym both for the life cut short and for the grief of those left behind. Not just a mere prop, the shoe uses its non-human viewpoint to underscore the loss of human life. Through the present absence that they conjure up, ownerless shoes function as silent witnesses to the unspeakable tragedy, reminding the audience of the personal costs of collective action and evoking a haptic sense of the past that is still alive in Gwangju.

Beyond Gwangju, shoes have continued to exercise symbolic force in South Korea’s fight for democracy. On June 9, 1987, during an anti-government protest in front of Yonsei University, a tear gas canister fired by the police struck university student Lee Han-yeol. As Lee collapsed, his blood soaked one of his sneakers, which fell off and was later retrieved. The other shoe was never returned to its owner, who died soon from injuries. The incident became a catalyst for the June Democratic Uprising, which paved the way for South Korea’s first democratic elections after nearly three decades of authoritarian rule. On July 10, 1987, The Chosun Ilbo featured an illustration of his sneaker on its front page with the headline, “Lee Han-yeol’s Final Farewell . . . A Million Mourners.” Once again, shoes carry forward the steps of those who had courageously dedicated their lives to the struggle for change, opening up a path for history to move forward.

In 2020, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the May 18 Democratization Movement, the Gwangju Biennale Foundation organized a special exhibition titled to where the flowers are blooming. The exhibition began in Seoul and then traveled to Taipei, Cologne, Gwangju, and eventually Venice, its contemporary and international circuit a reflection of how the spirit of May 18 continues into the present and is sent out into the broader world. Just as the owners of those abandoned shoes empower us in the present to continue the march forward, this exhibition, too, wandered in search of Gwangju’s spring, continuously reaching toward the blooming flowers.

In fact, the exhibition title “to where the flowers are blooming” comes from Han Kang’s Human Acts, a novelization of the Gwangju Uprising and its traumatic aftermath. One of the novel’s central protagonists is Dong-ho, a middle school student murdered by state violence when soldiers began to fire indiscriminately at the young protestors walking toward them in surrender. Chapter six focuses on Dong-ho’s lingering presence after his death, as his grieving mother wanders around in search of his traces. She recalls how, on their walks along the river, her young child had “disliked the shadowed places where the trees blocked out the sun” and always wanted to—here, we are given Dong-ho’s voice—“go over there, where the flowers are blooming.” While the chapter is narrated from the mother’s point of view, it concludes with these words from Dong-ho, underscoring the ongoing presence of his spirit in the material world. The remnants of the past, residing at the boundaries of linguistic expression, strive to speak to us in their own way.

In chapter two, Human Acts more explicitly engages with the idea of spiritual witness by adopting the point of view of Dong-ho’s deceased friend Jeong-dae, whose spirit lingers on after his physical death. As Jeong-dae looks on, soldiers discard the bodies of the dead—including Jeong-dae’s own—in an empty lot, stacking them on top of each other and setting them on fire. Though detached from a physical form, Jeong-dae’s ghostly presence bears a kind of witness that transcends the boundary between life and death, visible and invisible, expressed and silent, material and spiritual. In thus depicting those who have lost their lives during the Uprising, Human Acts solicits what Ji-Eun Lee describes as the “secondary witness” of readers, who are tasked with an ethical obligation to remember and retell. Would that then allow the souls of the deceased to truly be “free,” in the words of Jeong-dae, “free to go wherever we would?” To where the flowers are blooming?

The exhibition that borrows those words for its title provides an answer to this question. Many of its artworks bring back the spirits of those who have lived through the violent upheaval, as in Ahn Chang Hong’s Arirang Series (2014-2017) and Noh Suntag’s Forgetting Machines (2006-20). Interpreting ordinary people as the true agents of history, both Ahn and Noh place them at the center of their work. In “Arirang 2014’1,” Ahn paints over an old black-and-white photograph of what looks like a wedding. The individuals have their eyes closed, with some holding bouquets and others baskets. Tiny yellow butterflies interspersed with red flicks of paint reminiscent of blood are superimposed all over the figures, invoking both violence and hope in the face of tragedy. Expressing a similar sentiment, Noh recaptured with his camera the funerary portraits on the gravestones in the Mangwol-dong Cemetery, the old burial site for victims killed during the May 18 Democratization Movement. Through the intervention of his own documentary apparatus, which presents the faces of the deceased as faded and distorted, the artist raises questions about the relationship between past and present, remembering and forgetting.

In both Ahn and Noh’s work, closed eyes and obscured faces testify to a marginalized history that demands redress. Like the souls of Dong-ho and Jeong-dae, they bear witness to something that we urgently need to see, so that they, like us, can fly with the butterflies to where the flowers are blooming. It is in this spirit that the exhibition concludes with Choi Sun’s Butterflies, a project inviting the participation of visitors from different walks of life. In this collaborative work, participants drip blue ink onto a vast white canvas and use their breaths to disperse the ink, creating a striking visual that captures and preserves the presence of each individual within a diverse but collective whole. Breathing new life into the memoirs of Gwangju, the visitors welcomed by the exhibition’s long journey around the world thus continue the paths first forged by the owners of those shoes invoked and memorialized in the 5.18 Archives.

The anthropologist Alfred Gell has argued that material “things”—a category that includes plants, animals, and works of art—are not merely passive entities but can “emanate” social agency through the relationships that humans enter into with them. Whether retrieved from everyday life, preserved in museums, inscribed in books, or depicted on screen, the shoes, flowers, and butterflies associated with Gwangju embody, extend, and amplify human emotions, identities, and relationships in both the past and present. We can thus read these scenes of Gwangju as complex networks of meaning making in which, to borrow the words of David Morgan, “people, objects, environments, histories, words, and ideas” interact to preserve, construct, and perpetuate the memories of the Gwangju Uprising. The public, who bring their own histories and experiences, is invited into such scenes as agents in their own right. As Simon J. Knell has suggested, every art object that yields itself up for perception “is actually two, one tangible and real but not always present, the other intangible, the product of experience and negotiation, which seems to us to be the real object but is not.”

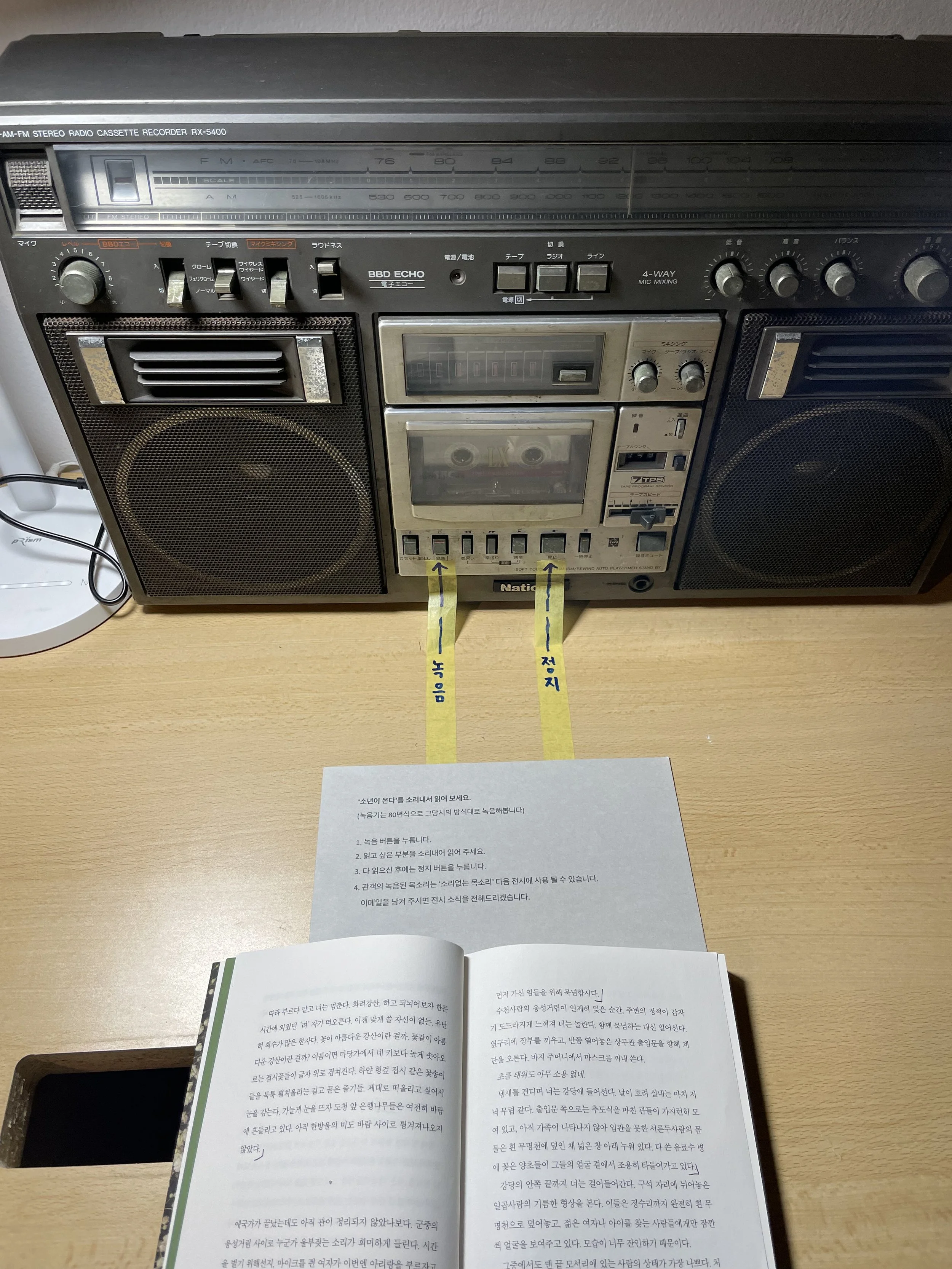

Thus, Gwangju’s legacy lives on not only in the documentation of events but through the ongoing transmission, interpretation, and retelling of its multimedia narratives. The exhibition Silent Lament, organized by The May 18 Foundation and hosted by Gwangju’s May 18 Memorial Cultural Center in October 2023, offers a moving example of such meaning making. The exhibition is anchored by a video installation in which six “May Mothers,” a term for the women who lost family members in the Gwangju Uprising, recite paragraphs from chapter six of Han’s Human Acts. Additionally, in a designated area within the exhibition space, visitors are invited to participate by reading excerpts from the novel’s first chapter, which narrates Dong-ho’s story, and to record their voices using an actual 1980s recorder that had been used during the May 18 Democratization Movement. Physical objects, multimedia production and representation, and the humans who survive as witnesses and who come as witness-bearers thus come together in a complex scene of transmission and augmentation, each acting and being acted upon by others to give voice to those who have been silenced, so that their lament is no longer unheard but rings out in time.

The present generation hears Gwangju’s lament and takes it to heart. On December 14, 2024, 11 days after he declared martial law, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol was impeached by the National Assembly. On April 4, 2025, the Constitutional Court of Korea upheld the impeachment and officially removed Yoon from office.

Memories of authoritarian rule during the 1970s and ’80s and the struggles against dictatorship that ensued laid the groundwork for modern democracy. Those historical precedents empowered the people today to respond swiftly to the martial law crisis. Like the protestors in the May 18 Democratization Movement, citizens calling for Yoon’s impeachment prioritized public order and marched in solidarity. And like the past generations who sang minjung gayo (protest songs) to rally the crowds, young protestors used K-pop music to energize and engage participants on cold days. Images of Gwangju citizens sharing rice balls on the streets in May 1980 have become, nearly 45 years later, scenes of Seoul residents distributing warm drinks and food for free. As Yonhap News TV reports, this is a story of “parents who built democracy and children who defended it.”

Four days after Yoon’s declaration of martial law, Han Kang, who became in 2024 the first Korean to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, delivered her Nobel Prize lecture: “Later, as I was writing what would become Human Acts, I sensed at certain moments that the past was indeed helping the present, and that the dead were saving the living.” Ə