This isn’t Stray Kids fan fiction, but…

. . . but if it was, the tags would be: Stray Kids (Band), Hurt/Comfort, Found Family, Australian Chan and Felix, Original Character (OC), Canon Compliant. In which I (OC), a young Asian writer, break into and navigate the harsh publishing world through the power of “Stray”-ness.

Or: three times Stray Kids taught me I could belong + one time they showed me I shouldn’t.

number one: belonging in my culture

In the first book I ever wrote, I was a 13-year-old boy from Nowhere, America. “Nowhere” because I was 10 years old struggling with geography, “America” because I was only familiar with Hollywood action movie settings, and “13-year-old boy” because that was all the representation I knew.

It would take me four years to begin a manuscript with a white female protagonist. It would take me another five years to write a manuscript with a Singaporean female protagonist, and I’d later go on to sell that manuscript for publication with a Big 5 publishing house.

Hey, Cam, congratulations on finding yourself!

Not quite . . . I wrote my debut fantasy novel while pent up in Singapore with my parents, driven only by sleep-deprived creativity and an unrealised childhood dream. But by the time I queried my novel, attained a literary agent, revised with my agent, sold the book, and revised that with my editor, I was nearly three years into my Law degree in the UK. It was like taking the husk of a young adult, only partly full of half-baked identity and warring philosophies, and filling the rest of the empty space with a new culture. I was a bottle of tradition and a jumble of new experiences shaken up like Coke and Mentos, ready to implode.

I remember the countdown to my implosion. I attended a flat party with other Singaporeans. I brought bolognese; a friend made cottage pie; and someone else made stir-fried spinach, Chinese style. As we drank, I spoke about school and truncated my sentences like I would in Singapore, shedding the full sentences I’d painstakingly learned to craft when speaking to the British. My friends responded in kind. “Everything’s fine lah,” my friend said. “But we should ju an si wei.”

Ju an si wei. I didn’t know the words, though I recognised them enough to know they were Mandarin, not dialect, and I took a swig of vodka orange juice. There was a burn in my chest that wasn’t alcohol or indigestion. There was a heat in my ears that wasn’t insobriety, but shame. Ju an si wei. I turned these words from my mother tongue over in my head and came up hopelessly empty.

So I said, “Yeah, it’s fine lah.” I emphasised the lah. Didn’t know why I felt the need, a desperate urge, to prove that I know what you’re saying. To prove that I’m Singaporean, too.

It didn’t make sense that I was so upset. Back in Singapore, there were so many Mandarin words that I didn’t know—what was the difference now, when we were hundreds of miles away from home? And why did it feel like a part of home was slipping away from me? I had been tied to Singapore like this: conversing in Singlish with our hawker stall vendors while buying three-dollar dishes; braving the scorching heat with squinted eyes and a face of sunscreen (but no protection for my arms or legs); reveling in our pristine and punctual public transportation system.

I guess when my feet are no longer planted in familiar land—when the ground smells different after the rain, when the storms are meek and muted, and when the train is a grinding journey of death through London’s underground system—then there is only myself to remember home by.

My dorm room was small. The walls were thin and the heavy doors slammed shut on their own with an obnoxious boom. I studied with headphones on, YouTube playing softly, straining to grasp the doctrine of sovereignty and promissory estoppel while Stray Kids compilations ran in the background. But suddenly I heard Chan say, “G’day, mate!” This was quickly followed by Felix’s “G’day mate!” and then a burst of laughter.

I paused work to rewatch the clip. I knew both men were Australian, knew that Felix moved from Australia to Korea far later than Chan did and as a result was more “tied” to his Australian roots. But listening to them repeat the words and emphasise Australian slang like I’d done with Singaporean slang just earlier this evening, I thought, do you feel it too? Does it empower you the way it does for me?

Felix has always been Australian first, Korean idol second. The production team of Stray Kids, the 2017 survival show that birthed the group, often drew on and edited moments where Felix struggled with Korean to highlight exactly how foreign he was. Felix is famous for having learned Korean and immersing himself in Korean culture only after joining Stray Kids at 17. Chan, on the other hand, spent most of his adolescence in Korea—yet as he spoke about Australia, where he had lived until 13, there was a deep fondness, an ache that felt frighteningly familiar.

I related to Felix when I first moved to London, missing home and struggling to come to terms with a new culture. Was it so wrong to want to retain my Singaporean identity? To keep my slang, even if it meant other students asking me to repeat myself again and again? Felix was initially eliminated from Stray Kids, his limited Korean impeding his ability to rap clearly. Throughout the survival show, his dedication to learning Korean—and his success at doing so in mere months—was remarkable. It was the perfect example of having to assimilate to an unfamiliar culture just to survive.

But Chan’s longing for and pride in Australia gave voice to the emotions Singapore had left lodged in my chest. It took losing everything I’d taken for granted to realise how deep my sense of national pride ran.

In Singapore, we have “National Day”, where we wear red to school and belt patriotic songs for several hours before being sent back home to watch the evening festivities with our families. That had been as strong as my national pride went. But now I know how special we are—our food unique to our country, our buildings scraping our scorching skies, our way of communication so blunt but so efficient. When I speak about it with my friends, do they hear the ache in my voice?

Chan has admitted to keeping Australian seawater by his bed and keeping live footage of Australian beaches running in his background—anything to remind him of home.

I used to hate the sun because I burned so easily. But god, I’d give anything to be scorched again, if only the pain and heat could take me home.

number two: belonging in my passions

One of Stray Kids’ most painfully relatable songs for me as a young author is “Social Path,” which describes the trials and tribulations of spending your youth chasing ambition. The song begins with a layered chant from all eight members: “Gave up / My youth / For my / Future.” In an introduction to their album ROCK-STAR, Chan specifically discussed these lines. “I wanted to try writing my story, in hopes someone else relates,” he explained. “The members came to my mind while writing it, because I thought they’d feel the same way.”

Pursuing publishing meant missing out on school balls and friend outings. It meant fighting the pressure to follow more conventional goals and resiliently pursuing something none of my peers were pursuing. Why was I staying up late re-reading words I’d already burned into my brain, while my classmates applied to law firms or attended networking events? Why was I agonising for hours over line edits and other seemingly trivial manuscript details, while my friends went out or clubbed on weekend nights?

I burned my youth to feed the flame of my ambition and consequently found no solace among my university friends, who were pursuing wholly different interests: highly coveted internships, legal careers, corporate lives.

But I found company in Stray Kids’ journeys as idols. The Stray Kids members led lives fraught with “stray-ness.” Chan left behind his friends and family in Australia, diverging from the typical path at just 13. His famously long training period also meant he watched many new friends leave him, some giving up and others debuting before he did.

HAN was 15 when he auditioned for JYP Entertainment. He had attended an international school in Malaysia and was subsequently homeschooled, experiences that set him apart from both his Korean and Malaysian peers. At the time of his audition, he had only recently moved from Malaysia, carrying with him a promise to his parents that he would return to Malaysia if he wasn’t accepted into an entertainment agency within a year. Hyunjin was street-cast, and his lack of formal training showed in both his singing and dancing. His peers dismissed him, saying he would debut on visuals alone and therefore not need to work as hard as others. Seungmin dreamed of being a baseball player but suddenly pivoted to singing—I think about his journey often, about the fact that he’d been walking down a path already laid out before him and still chose to go astray. I.N.’s first job was becoming an idol at 16, stepping away from the regular adolescent life that his non-idol peers experienced.

This stray-ness is reflected clearly in their music and interviews. “Social Path” is about giving up youth and community to forge one’s own path, a painful truth that all the members resonated with. Hyunjin explained that the members have been together for nearly a decade, and the song melded all those feelings of cheering each other on.

Why are you comparing yourself to global idols, Cam?

To say that I felt my experience mirrored in their careers would sound too grand, but to say otherwise would be a lie. Before my book deal, I was acutely aware that I was wasting my youth on abstract dreams. All the times I avoided socializing to revise my book and all the law firm applications I passed over to prioritise my self-imposed manuscript deadlines—these all gradually nudged me away from my community. I was 18, then 19, then 20, and still I had never gone to a club or found a group I hung out with more than once a week.

I had very few close friends, but sacrificing my youth for my ambition also meant sacrificing the relationships I was supposed to be building. I felt alienated, until I found a driving force in my stray-ness.

Aside from the call in “Social Path” to be an “alien of the town” in the pursuit of one’s dreams, HAN’s “Alien” also gave me an anthem for not belonging. The song’s lyrics describe feeling like an “alien on this earth” and not seeming to “belong anywhere by myself.” Upon the song’s release, HAN commented that this self-composed and self-produced track contained his “worries and thoughts, including feelings of not belonging anywhere.” The path to the top was lonely, and when there was no end in sight—as there never was when one was pursuing an unconventional dream—would it be enough to know that there were others treading the same lonely path?

After a recent arena performance of “Social Path,” Chan began a ment by saying, “We really gave up our youth for our future . . . ” He trailed off, his eyes glistening with tears. Changbin placed an arm around his groupmate. “This is our youth,” he responded. “Thinking you’ve sold your youth is like living in an impossible dream.” As in: Chan couldn’t have had the traditional definition of youth and still attain the success he did with Stray Kids.

I watched the moment unfold before me. I was sleep deprived and exhausted. I’d had three school assignments due over the course of the last week, and my next round of manuscript revisions were due in a week.

I could do it. I was still in my youth, and Changbin was right—there was no youth to be lost when I was walking along a path I had chosen so fervently.

number three: belonging in myself

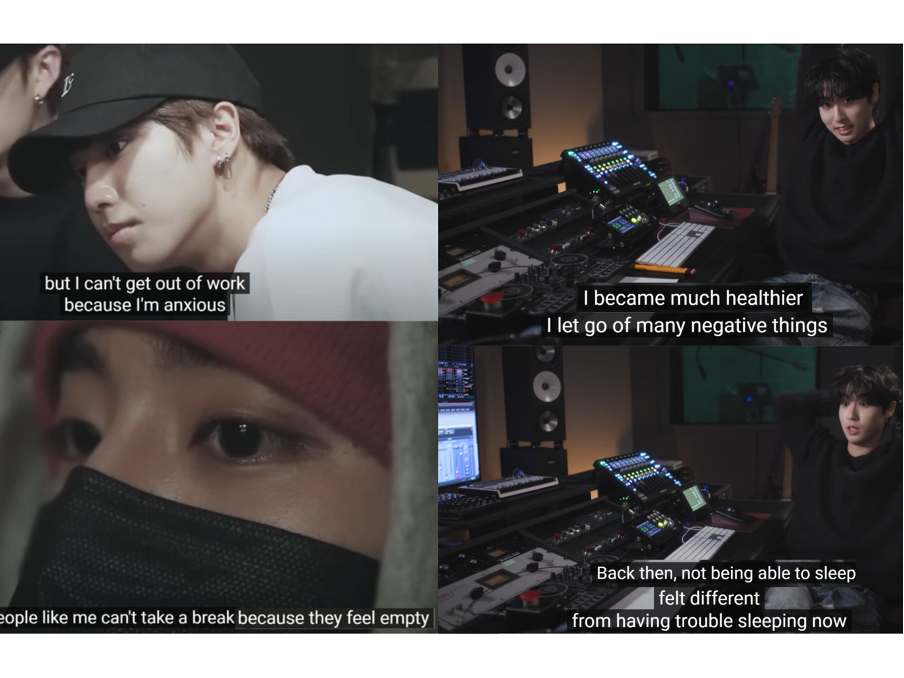

“I can’t stop working because I’m anxious,” HAN admits with a sheepish look.

It’s still early in their career, and he’s speaking about producing music with 3RACHA (the music production subunit of Stray Kids, consisting of members Chan, Changbin, and HAN) even while they were busy touring the US.

I’m staring at my screen, my dozens of pages of law readings lined up in my Google tabs, five Google documents open as I toggle between completing work for school and revising my manuscript for submission to publishers. My to-do list is cluttered with tasks from the school club where I am a social media manager, my weekends are blocked out for shifts at the posh local gastropub, and I am adjusting to living alone.

HAN’s in the middle of explaining that his self-produced and self-composed song “Sunshine” is about “finding the ideal break.” “People like me can’t take a break because they feel empty,” he adds in a sombre tone.

And I’m finally putting together all the puzzle pieces of the person I thought I was—hopeful, hardworking, passionate—and stepping back to find a picture I hadn’t realised I’d made—alone, desperate, empty.

So.

I guess this is where all the running and fear of stagnancy has come to.

I have a horrible memory and a brutal work ethic. The month before exam season, I was pulling 14-hour study shifts. The remaining 10 hours of my day went like this: two hours for eating and meal prep, one hour for showering, one to two hours for commuting to my study spot, one to two hours for rest, and about five hours of sleep. Spoiler alert: that amount of rest was not enough.

I remember the moment I felt myself start to fray. I was pushing myself to focus in the school library, two weeks before my exams. My parents were calling me, but I couldn’t pick up my phone. I didn’t want to leave the library and risk losing my spot to the dozens of other students hunting for spaces during exam season. My phone screen lit up with my dad’s name—I hadn’t spoken to him in days, though I usually called him daily. There really wasn’t much else I could do. I cried looking at my dad’s name, and I texted him that I was studying again.

“Good luck!” he replied, and at that moment I was overwhelmed by a sense of bone-deep exhaustion and loneliness. My parents didn’t even know that I wrote creatively, and through the stress of the exam season, I had rejections rolling in from querying.

My breaking point came in the aftermath of that incident, spurred by a particularly kind and detailed rejection. An agent explained that they had a vision of my book that involved much more complex world-building, and that it wouldn’t be fair to take me on unless I agreed. I saw their vision, but it was much more academic than I’d intended my book to be, and they had guessed right—that wasn’t something I aligned with. It would, however, objectively make the book more intelligent. Perhaps. That was probably what hurt me the most—the fact that even I thought it might elevate the book. While I didn’t want to change my book into something it was not, I was plagued by the fear that, maybe, that book was not good enough. Maybe it was never meant to be published at all.

I figured I was done.

When I stopped querying—stopped writing completely—it was not only because I was buried under coursework. It was because I no longer saw a future in it. My stagnancy frustrated me, warring with my desire to push myself to the brink just to be better.

I felt so alone in my struggle. I didn’t tell many people about how stressed I was about writing. Few people even knew I wrote, let alone could empathise with my frustration.

But one of my favourite HANpop songs (as STAYs affectionately call songs written by HAN) is “SLUMP,” a song about feeling like one is always falling behind. There’s a stanza that goes: “Everything feels the same as a year ago / Please, do better / So you don't have to be ashamed wherever you go / So that I can smile and be proud when I look at myself.” I related achingly to everything feeling “the same as a year ago”—even when I knew it wasn’t rationally true. I was advancing in my degree. I was still meeting my deadlines.

Still, I was stuck on how it was 2022 and I didn’t have an agent, and then it was 2023 and I still didn’t have an agent, so what had I really done through the year? And why did it feel so horrible? The lyrics helped me name why stagnancy made me restless: I felt like I was not moving forward but that I had to if I wanted to be proud of myself.

“SLUMP” pushed me to keep going in the midst of feeling stagnant. If even a member of a globally acclaimed boy group would feel this way, then surely the emotion was irrational. Stray Kids’ dogged pursuit of excellence in their early 20s stood out so much to me. Finally, I’d found celebrities I could relate to. HAN brought the issue to my attention, and his members helped me feel like I wasn’t alone.

So I resumed querying and writing, comforted by the thought that my haunting fear of inadequacy was just part of being a creative. And as I wrote—and finally signed with an agent—I became more open with my friends.

“Have a writing deadline this week,” I’d tell them, “but I’m free next Tuesday!”

And they would wish me good luck, and suddenly none of it felt very lonely anymore.

As I grow, and Stray Kids enter their mid-20s, there has been a significant shift. In a recent interview, five years after confessing to feeling empty, HAN proudly states that he has “become much happier” and “let go of many unhealthy things.” This did not happen overnight. Earlier in the year, Stray Kids shared that HAN had gone off the grid for a day. HAN explained that speaking to the members after his disappearance made him realise he was genuinely valued, and he’s been far happier since. HAN has clearly found belonging in himself and settled into his identity as a creative.

HAN’s interview was quickly followed by his solo release, “Hold my Hand,” written as a letter to care for and assure his past self that it would all turn out well. HAN admits that while he might have needed the struggle to get to where he is now, he wishes he could’ve been there to hold his own hand.

I imagine myself in the future. When I sit down for long hours now, my back twinges with unnatural pain. Sometimes I write into the witching hours, and my eyes burn with exhaustion the next day. After six-hour writing sessions, my wrists ache with movement.

I remind myself that while there will always be more words to write, I have only one body. I picture future-me looking back on this moment and wishing I had protected my health instead of chasing a goal I wouldn’t even remember.

I close my computer, and I go to sleep.

+ number one: we shouldn’t belong

It was to be a private event, an exciting chance to meet other authors, book influencers, and staff from my publishing team. I waited an entire day to respond to the pretty invite sitting in my inbox, only because I was so eager that I could’ve replied on the spot. But I wanted to seem nonchalant. I had a life outside of publishing, of course.

I counted the days down, spent an hour trying on outfits until I found the perfect blue top and cargo skirt, then paired them with my tallest combat boots. I couldn’t have people thinking I was short.

It was late evening when I shuffled into the room, accepted the badge that said “Author,” and floated uncertainly among all the industry professionals. People were kind when they saw my badge, when they caught my lost expression.

Pink posters, each printed with my publisher’s logos and a list of authors in attendance, lined the walls of the bar that had been reserved for the event. I stood in front of one of these posters for so long, staring at my name and the brief synopsis of my book that appeared next to it. It had never felt more real, more tangible, than when I ran my fingers over the freshly printed poster, black ink on a baby pink background.

I mingled with everyone, making sure to bury my Singaporean accent and trotting out the British-American mix I’d picked up (“It’s not a British accent,” my English friend once said, “but it doesn’t sound Singaporean either . . . it just sounds like you learned English from somewhere outside of Britain.”)

“Did you go to an international school in Singapore?” Someone—I don’t remember if it was a book influencer, author, or staff member, I was so surprised—suddenly came up to me and asked.

I said, “No, but why?”

They smiled kindly. It was so gentle, so flattering. “Your English is so good,” they said. “I thought you must’ve gone to international school.”

I was so confused. Where would I even begin? Should I explain that Singaporeans, especially the younger generations, spoke primarily in English? Should I ask if they thought that my English was “good” because it sounded not Singaporean but more like the British accent they were used to? Were they truly talking about language ability, or were they just saying, you fit in with us? I hadn’t used any fancy words, and I doubt that I was using particularly elaborate syntax. Did they just mean that I was eloquent? Did they consider that I only sounded this way to them because I’d spent two years unlearning what was considered well spoken in my culture? Did they realize that if I had spoken this way to people in Singapore, it would sound so unnecessarily indirect that Singaporeans might consider it a waste of communication time?

Another horrifying thought hit me: maybe I wasn’t even culturally very Singaporean anymore. I had changed my lexicon so much since moving here. I used to be so confused when people said “cheers” as a substitute for “thank you.” We only ever used “cheers” in Singapore when we had drinks in hand, and the word would always be followed by raucous clinking. Now I use “cheers” all the time, relishing in how successful I am at fitting in, as if I were a spy who pulled off a grand espionage job.

But if I have shed so much of my culture to fit in, what happens when I’m the only Singaporean in a room? Do they think all Singaporeans speak like me? When people hear I’m Singaporean and ask for food recommendations for their trip, do I explain that I wouldn’t know because the country seems to have morphed a little more every time I return?

A few months after the event, even my non-Singaporean flatmate joked, “Can you even hear yourself? You don’t sound Singaporean anymore!” And I laughed—because it was a joke, but also because it was true. My mix of American and British had been influenced by my flatmate from Hong Kong and my British friends. I told myself I was code-switching to communicate with my flatmate, but later I lay in bed speaking aloud to myself to figure out which accent I most instinctively used. Spoiler alert: not Singaporean.

The night after, I spent three hours reading the dialogue in my manuscript, first in a Singaporean accent, then in the accent I’d become accustomed to in the UK. I was seized with a paralysing fear: what if I didn’t sound Singaporean enough? There’s a stereotype of the International Student Who Left Home and Came Back Enamoured with Western Culture. Would Singaporeans feel that way when they read my book? It’s a fantasy set in Singapore, and I’d initially written it as a love letter to Singapore. But at some point, between revising it with a UK editor and spending time in the UK, I knew my lexicon had shifted to fit theirs, and suddenly it felt like we were all outsiders to this Singaporean book. And I thought, how do you write a love letter to someone you don’t know anymore?

I spiralled for so long. I scrolled through Goodreads reviews of a Singaporean debut where readers tore the Singaporean author apart for not being “Singaporean” enough, and I didn’t understand some of the points they raised. Some things were so fickle. It terrified me—publishing was an industry where my cultural identity would be tied to my reception as an author. I’d already changed several Singaporean references because my publisher flagged it for being too inaccessible for English audiences. They were all simple—a “pick-up point” in Singapore was a “drop-off point” in England. Council housing in England had a vastly different connotation from council housing in Singapore, and it shifted the readers’ perception of my characters.

I was too Singaporean for our Western audience. I was too Western for my Singaporean audience. I feared constantly that my characters were speaking like me—someone divorced from her country, someone pretending to be Singaporean when I’ve forgotten which buses go to my Singaporean home and which words to use when the hawkers snap at me in Mandarin.

There’s a very distinct and constant struggle to be proving myself, all the time. From the moment I began querying, I knew the odds would always be stacked against me. BIPOC people weren't necessarily favoured by acquisition boards or marketing teams. At one point, I nearly gave up. What if people only read my book to check their “Diversity Pick of the Month” box? I wanted to exist as a fantasy author without having to always be a spokesperson for my culture, and it was so exhausting that I stopped writing.

It was Stray Kids’ insistence on stray-ness that broke me out of my complex. Changbin once said that 3RACHA constantly felt pressured to create new music styles, then worry that they would have nothing else to show after releasing them. He explained wanting to not bore people by releasing the same kind of music but also being burnt out from the pressure to constantly create something new to impress their fans. At some point, their fear of catering to an invisible future audience began impeding their ability to create art, and didn’t that sound so familiar to me?

During the introduction interview for their album 5-STAR, Seungmin explained that when Stray Kids first debuted, “all our songs were about feeling lost . . . it was focused on ‘stray.’” I.N. and Changbin later added that now, Stray Kids focuses on “Kids”—on embracing the novelty and freedom of youth. Their 5-STAR album marked the beginning of a series of albums with grandiose titles (5-STAR to imply a top-rated album, ATE in reference to the internet slang for performing exceptionally well), and the members agreed that these titles also brought the pressure of producing music that lives up to the name. But Lee Know also acknowledged that though they didn’t know which direction to take at first, it helped massively that fans were beginning to view Stray Kids as their own genre.

And this is true. In both interviews and through the music they’ve produced, Stray Kids has acknowledged their desire to stray from regular pop. Their songs range from EDM to ballad to hip-hop, often mixing multiple genres at once. In a music scene dominated by predictable clap tracks and digestible beats, Stray Kids released “Walkin on Water,” a callback to 90s hip-hop, a.k.a. a genre that had not been charting on the billboards—until their release.

Their earlier 2024 album ATE featured a Latin-influenced, reggaeton-reminiscent title track. ROCK-STAR, the album before that, built its title track around heavy Afrobeat and phonk elements. No two of their songs sound alike, and yet there’s a trademark Stray Kids energy and music sampling that remain consistent throughout: the sound of dominoes falling in “DOMINO,” the echoing knock of a door in “Back Door,” the crawling, string-plucked ascending notes in “VENOM,” the snake charmer whistle in “Charmer,” and more. The creativity of their producer team shines through the beats and the lyrics of each song.

In a comment about “S-Class,” their title track for 5-STAR, Changbin and HAN agreed that it was “difficult to decide on one genre” for the song. Featuring a mix of genres, “S-Class” begins with whistling, rap, and electro, before its BPM shifts completely into old-school hip-hop in the second half. The two members from Stray Kids’ producer team said, “Is ‘S-Class’ not a genre unique to Stray Kids? The genre is Stray Kids.” Just listening to their major tracks is enough to help one understand what they mean. Tracks such as “CASE 143,” “God’s Menu,” and “Thunderous,” with their frequent beat changes and rapid switches between rap and melody with little transition, can feel like multiple songs stitched into one. This obviously has not flown well with everyone, earning Stray Kids the label of “noise music.”

But it sketches a picture of a group who’s trying it all out: dipping into every genre they can find, boldly experimenting and blending even if it draws criticism.

It’s not that I’m inadequate for either my Singaporean or my Western audience. I am a story that straddles both cultures, and what’s so wrong with trying it all? So what if I didn’t belong?

Congratulations on finding an identity, Cam!

I have not. But “Stray” isn’t being lost, it’s having the freedom to wander—and I am so, so Stray.

Notes:

I’ve been reflecting a lot on my book deal—on all the arduous work and mountainous self-doubt that I slogged through just to pursue publishing. I think about how I’d change none of it, because the point is that I got here in the end. Except it’s not something I could’ve known then, and it doesn’t erase the blood, sweat, and tears I poured into it. Stray Kids did not save me, but they made my journey easier. They took my hand and supported me as I navigated my culture, community, and sense of creative identity as a young Asian author.

My closing image? As HAN so prophetically sang, “I know that on the final page there will be an incredible plot twist . . . so hold my hand now?” Ə