The Modern South Korean Revenge Fairytale: Women in Cancer and Love

Korean dramas about cancer are often not really about cancer. In the iconic Autumn in My Heart (2000), whose international success helped launch the Korean Wave, the doomed love between Yoon Jun-seo and Yoon Eun-seo becomes even more tragic when Eun-seo is diagnosed with leukemia. Raised as siblings after an accidental swap at the hospital, Jun-seo and Eun-seo’s quasi incest is neatly solved by her death. In Wonderful Life (2005), a leukemia-stricken child becomes the plot device for her parents’ reconciliation, as Han Seung-wan and Jung Se-jin, who had been pressured by their families into a shotgun marriage, come to learn the value of family. Finally, in Coffee Prince (2007), a grandmother secretly dying of cancer and hoping to ensure her family legacy compels her immature grandson Choi Han-gyeol to run a coffee shop, where he hires and eventually falls in love with the reliable Go Eun-chan. The common feature in these cancer narratives is that there is not much about the experience of having cancer itself.

As a widely recognized disease that needs no introduction, cancer functions as a convenient plot twist. Since many K-dramas focus on romance and family, that plot complication often raises questions about the role women play in not just biological but also social reproduction. In the 2005 K-drama My Lovely Samsoon, for instance, the gastric cancer that the (conveniently) second female lead is diagnosed with disqualifies her from being marriage material. While the K-drama explores how cancer can lead to social death for women, it subordinates those insights as a subplot whose main function is to facilitate the romance between the protagonists.

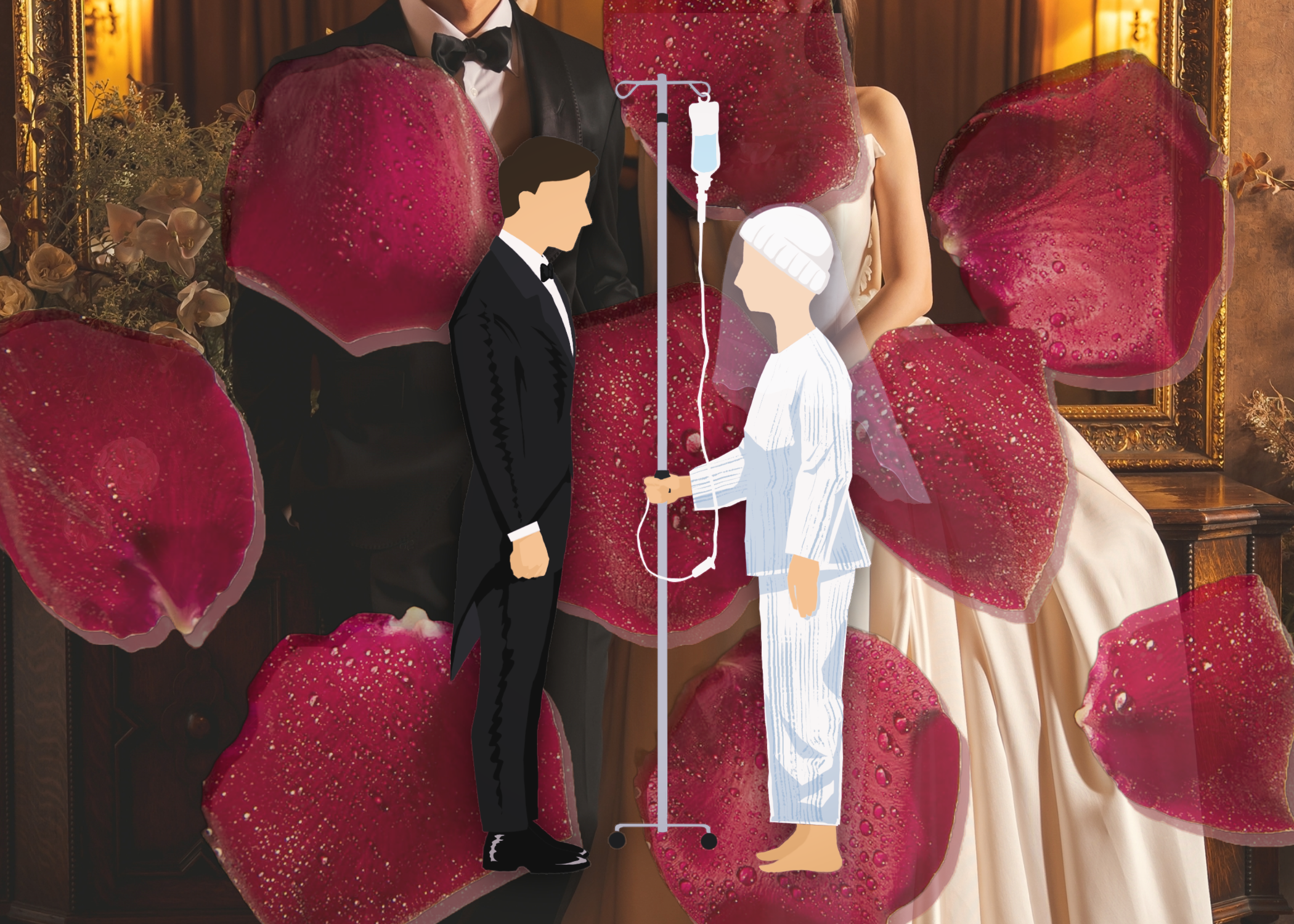

However, the slow creep of neoliberal values into everyday life has introduced a new kind of cancer narrative into the K-media landscape. This narrative refuses to accept cancer as pure tragedy. Rather, cancer becomes an opportunity for the women to re-evaluate their lives, name the gendered oppression that they experience, and make consequent changes in light of their newfound awareness of mortality. While this narrative turn might seem liberatory, it ultimately functions as a form of vicarious revenge that women audiences can enjoy as they watch fellow women on screen act out against the men in their lives. Using Life Is Beautiful (2022) and Marry My Husband (2024) as examples, I trace the paradoxical way in which contemporary Korean cancer stories resist only to ultimately capitulate to the oppressively gendered conditions of life within a neoliberal patriarchal society.

Let us first examine Life Is Beautiful, a musical comedy film directed by Choi Kook-hee. The joint protagonists are a middle-aged married couple. The wife, Oh Se-yeon, is unexpectedly diagnosed with terminal lung cancer and given two months to live. Her husband, Kang Jin-bong, seems to react with nothing but annoyance. The day after Se-yeon’s diagnosis, we see a slice of her life by following her daily activities. In the family’s regular morning routine, Se-yeon is treated like an inept servant by her husband and children, who make loud demands for housework without expressing any gratitude. One scene depicts Jin-bong throwing a shirt at Se-yeon and shouting that it is still damp; in the next shot, we see Se-yeon silently drying the shirt with a hairdryer. All three family members leave home without saying goodbye, nor do they greet her when they come home. At the end of a long day, Se-yeon bursts out in anger at her husband: “I’m practically invisible in this house . . . I quit!”

Se-yeon’s cancer diagnosis fuels her regret at having wasted her life serving an ungrateful family. Now, emboldened by her terminal illness, she makes outrageous, self-centered demands a wife could not ordinarily justify. Se-yeon demands Jin-bong’s help in locating her high school boyfriend, the only one whom she thought truly appreciated her. When Jin-bong refuses, she goes on a shopping spree to make up for all the presents her husband never gave her, serves divorce papers to Jin-bong, and tells him she intends to spend all their money before she dies. Jin-bong caves under these threats and drives Se-yeon around the country in pursuit of her quest.

Even though the trip is purportedly about the high school boyfriend, it functions as a way for Se-yeon and Jin-bong to discover their love and deep care for each other. A flashback montage shows a secretly terrified Jin-bong grieving for his wife but hiding his emotions from her. By the end of the trip, the couple is able to reconcile because Jin-bong starts showing his feelings more and Se-yeon’s resentment melts away. It turns out that what Se-yeon wanted was not a divorce or even a radical upheaval of the household, but simply acknowledgement of her labor. When Jin-bong throws her a farewell celebration, Se-yeon declares that she was happy to have lived for her family after all: “What makes me the happiest is realizing how much I was loved. Thanks to you, I had a great life.”

Returning to her old self-effacing self, Se-yeon directs attention away from herself and toward her family as she tells her husband to remarry and asks her guests to care for her children in her stead. The film then skips over Se-yeon’s death and cuts to Jin-bong as a single parent doing the exact same chores as Se-yeon once did, though he is clearly less capable: the food on the table is store bought; the houseplants are dead; the children are still ungrateful and Jin-bong, overwhelmed by domestic work and grief, has to take the day off from his work. As we see Jin-bong reminiscing and wishing he had been a better husband, the audience, too, can imagine how much our families would miss us without having to actually suffer any tragedy. Even though it is too late for Se-yeon, the audience still gets to imagine how their own unappreciative families might miss their unacknowledged work.

Although cancer first provides Se-yeon with an opportunity for reclaiming her autonomy, it eventually facilitates her return to the role of the self-effacing and grateful wife and mother. This is a regressive fairytale. Indeed, Se-yeon and Jin-bong are a couple that feels out of time in 2022. Even though Life Is Beautiful is set in contemporary Korea, the realism of the plot does not hold up on close examination. Se-yeon and Jin-bong start dating in college during the 1980s—their first meeting even parodies the meet cute from 1987: When the Day Comes—but their children are only teenagers in present-day 2022. Either they waited until their 40s to have children, or the family is a deliberate throwback to an older era. Their family dynamic supports the latter: Jin-bong supports the family on his income as a low-ranking government worker while Se-yeon is a stay-at-home mother. The jukebox musical also prominently features retro songs from artists such as Shin Joong-hyun, Kim Gun-mo, and Lee Moon-sae, who rose to popularity between the 1970s and the early 2000s. Just as the film’s music is nostalgic, its message is also nostalgic for the good old days. For Se-yeon, a thriving family is sufficient compensation for all her pains—in fact, what makes her happy is that her family is happy and healthy. Although her rebellion against Jin-bong and their married life seemed to support independence for contemporary women, Se-yeon’s contentment in the face of death shows that all she ever wanted was a little recognition for her household labor.

In contrast, the popular 2024 K-drama Marry My Husband does not settle for calm reconciliation but instead aims for the husband’s total destruction. The protagonist Kang Ji-won is a terminal stomach cancer patient who discovers that her husband Park Min-hwan and her best friend Jung Soo-min are having an affair. When Ji-won confronts Min-hwan, he shoves her against a glass table and ends up killing her. In the moment of death, Ji-won is magically transported ten years into the past and granted the chance to live her life again. Ji-won realizes through trial and error that while the misfortunes that befell her are still bound to happen, they can be transferred to another person. Thus, Ji-won schemes to pass on her deadly marriage to her deceitful friend. Hence the title: marry my terrible husband and take all the bad things that happened to me.

The drama’s obvious appeal lies in its exaggerated tale of revenge, in which a woman whose confidence and career are gradually crushed by a series of abusive relationships—adulterous husband, toxic in-laws, sexist boss, and backstabbing friend—gets the chance to best them all in her second life. Through a series of flashbacks, we see representative snapshots of Ji-won’s marriage. Min-hwan’s mother, who repeatedly scolds Ji-won for failing to produce sons while her own spoiled (and sterile) son fails to defend his wife, is a cartoonish caricature of the evil Korean mother-in-law. Without consulting Ji-won, Min-hwan quits his job to trade stocks, and when he fails at it, he spends all day playing video games and violently refusing to do any housework.

As time goes on, Ji-won starts to experience stomachaches following stressful confrontations, clearly signaling that these stressors lie at the root of her developing stomach cancer. In her second chance at life, Ji-won believes she can avoid cancer by not marrying her husband and eating better. In one of the first scenes set in the new timeline, Ji-won recalls being diagnosed with stress-induced gastritis 10 years earlier. She wonders if this is the first sign of stomach cancer, gets a full health checkup, and resolves to improve her diet. Afterwards, her fear of cancer more or less disappears from the story.

In the end, Ji-won never gets cancer. Instead, the cancer jumps to her colleague Yang Ju-ran, who suffers a similar set of gendered stressors that originally caused Ji-won’s cancer. Ju-ran works under the same sexist boss and is similarly married to an adulterous, unemployed husband who refuses to help with housework. In addition, they have a young child entirely neglected by Ju-ran’s husband, which leaves Ju-ran having to juggle work and childcare. Ju-ran starts having the same stomachaches, but she gets diagnosed early, has a successful surgery, and gets a divorce, reinforcing the idea that when it comes to health, removing a bad husband is as important as removing a tumor.

In Marry My Husband, stereotypically gendered sources of stress are the only ones that cause illness. In the new timeline, Ji-won avoids marriage to her unfaithful husband and instead focuses on her career. Significantly, despite work challenges and long hours, she does not develop cancer. Although both domestic stress and demanding work hours adversely impact Korean women in real life, the show’s cancer plot critiques the former while validating the latter.

But avoiding marriage with Min-hwan does not mean Ji-won is no longer stressed. In addition to the unique stressors of figuring out time travel and manipulating her husband and best friend into marriage, Ji-won is determined to have a better career and takes on more responsibilities at work. She is often shown smiling as she puts in long hours on her work project. In one scene, she leaves the office extremely late and bumps into someone coming in extremely early; he is the man who will become her new future husband. Their common devotion to work is celebrated, their drive to success depicted as unquestionably good. In this universe, if stress comes merely from the desire to get ahead professionally, then fear not, it will cause no health problems.

Ji-won’s work project involves designing a line of fancy meal kits for single-person households. Her male boss scoffs at the idea, but it becomes a hit due to the number of people like Ji-won who are too busy with work to cook or marry but still want to eat well. This plot point reflects a broader cultural shift: for a woman, a successful career has grown to become more socially valuable than even marriage. Ji-won is 31 years old when she wakes up in her old life, but unlike Kim Sam-soon (the titular protagonist of My Lovely Sam Soon) at 30, she is deemed not an old maid but rather a young, successful woman. In fact, Ji-won stands out as a highly desirable partner due to her elite university degree, bank savings, and prestigious job. Part of the difficulty she faces in trying to get Min-hwan married to her best friend stems from his unwillingness to let go of a potential wife who can improve his social status and support him financially.

In the new timeline, Ji-won briefly gets engaged to Min-hwan again. Interestingly, her mother-in-law declares that there is no longer gender inequality in social life even as things must remain different at home. She holds the traditional view that women should perform housework and care for children, but she also approves of Ji-won keeping her career. When Ji-won slyly suggests she would be happy to quit work in order to focus on domestic responsibilities, her mother-in-law becomes worried about the cost of raising children. This captures for viewers the common problem of married women being expected to do what Arlie Hochschild calls the second shift, in which they continue to shoulder the burden of household labor after a long day at work. Meanwhile, their husbands only have to work outside the home.

In Ji-won’s second chance at life, she gets a makeover financed by her new friend Yoo Hee-yeon, who reminds her that physical appearance matters since “ordinary people judge everything on looks.” To be successful at her marketing job, Ji-won must also market herself as a beautiful and well-dressed person. While Hee-yeon helps Ji-won achieve this with her chaebol heiress money, Ji-won frames it as a personal investment in the self, declaring: “I will become happy with my own hands, my own strength.” Sharon Heijin Lee has observed that in contemporary South Korean society, “body work and the success it represents encompasses the neoliberal logics of competitiveness, self-management, and entrepreneurship to the exclusion of all else.” In alignment with these neoliberal values, Ji-won reads self-help books, leverages her knowledge of the future to invest in stocks, and regulates her diet to achieve stronger health and better looks for her work. For this hard work, she is rewarded with a cancer-free life and access to elite class status, as her story concludes with marriage to Yoo Ji-hyuk, the chaebol president of her company.

While Marry My Husband critiques gender inequality, it also suggests that women can fix these problems through individual effort rather than systematic change. The show’s fantasy scenario provide viewers with vicarious enjoyment as Ji-won satisfyingly crushes her old enemies to achieve a fairytale ending. In executing a gleeful gendered revenge, the show espouses neoliberal norms of self-responsibility, in which one’s own health and life are entirely up to individual effort. Cancer is thus less an unfortunate disease and more a symptom of the lack of self-care: when Ji-won embraces self-improvement and stops suffering in silence, disease does not dare touch her.

While at first glance this story might seem to be more progressive than Life Is Beautiful, that impression is deceptive. Ji-won might have a successful career as a single woman, but she is ultimately assisted by her new chaebol friends (Ji-hyuk and Hee-yeon turn out to be siblings). In fact, part of Ji-won’s successful revenge consists in marrying up—she not only abandons Min-hwan and his debts but marries into a chaebol family. In the final scene, set several years later, Ji-hyuk now officially leads the company where Ji-won also holds a high-ranking position; she is also mothering twin sons. Ji-won’s journey exposes the contradictions of neoliberal meritocracy: social mobility through hard work turns out to be a myth that is facilitated by entrenched privilege. In the end, Ji-won and Ju-ran can only escape their lives of gendered oppression through fairytale time travel and chaebol influence.

In both Life is Beautiful and Marry My Husband, cancer provides an opportunity for women to reflect and then pursue redress for the gendered injustices that they suffer. But the solutions that the shows offer do not tackle the structural problem of patriarchal capitalism: in one, a remorseful husband justifies the return of the self-effacing woman; in the other, submission to the neoliberal regime mystically solves the ills of household labor inequality. The failure to recognize how patriarchy and capitalism mutually reinforce each other perhaps constitutes the ultimate modern fairytale. Vicariously enjoying the onscreen catharsis, viewers forget that such stories not only leave intact the very structures that produced women’s suffering but further reinforce them. Ə