The Rise of the Murder Rom-Com

In recent years, Korean romantic comedy dramas have started to do something new. At this point, enough of these new rom-coms exist that I think they warrant their own subgenre. I call it the “murder rom-com”: a romantic comedy that follows the genre’s conventions while also weaving in a significant murder mystery plot. Consider, for instance, Dali and Cocky Prince (2021), a quirky romance between an art gallery heiress and a pork bone soup magnate that also includes a murdered father. Or Crash Course in Romance (2023), a love story between a star cram school instructor and a banchan store owner who must contend with the serial killer stalking their neighborhood. When the murder rom-com works, a deadly subplot can contribute tension to the romance and draw the protagonists closer in a meaningful way, but in less successful examples, audiences may feel deceived by the bait and switch.

The roaming murderer has long been a staple in Korean melodramas, procedurals, thrillers, and even the weekend makjang, a particular brand of over-the-top family melodrama that Korean television has become known for. But since the late 2010s, murder mysteries have increasingly appeared as subplots in rom-coms. While K-dramas have always played with genre hybridity, murder and romance do not intuitively go together, so this particular combination has sparked some criticism from fans.

Yet, I do not think this turn is out of the blue. In South Korea, growing social awareness of violence against women has occurred alongside an anti-feminist backlash. Against this backdrop, the murder rom-com emerges as a complex ideological response. While it acknowledges and works through gendered violence, the murder rom-com ultimately offers feel-good solutions that obscure the structural roots of the problem.

A New Kind of Hero

To understand the rise of the murder rom-com and its attendant gender politics, we have to consider how male leads in Korean rom-coms have changed over the past two decades. We see a movement away from the classic “Candy girl meets chaebol” narrative trope that dominated K-dramas from the 1990s and 2000s, in which a poor, hardworking, and plucky young woman crossed the path of a cold, handsome, and very rich man who was either the chairman of a company or on his way to becoming one. Although he would initially misunderstand and even despise her, creating the occasion for scenes of her humiliation and powerlessness, in time her beauty and goodness would bring him to his knees, and he would slowly succumb to his inconvenient and unseemly love for her.

This is a somewhat glib generalization, of course. Many of the genuinely romantic stories that use this trope are sharply critical of the ruling class and firmly aligned with the everywoman at their center. As We Jung Yi notes in her analysis of Korean television melodramas in the post-democratization, neoliberal era, these Candy/chaebol romances “both depict and decry social injustice and exploitation under the rule of neoliberalism.” Even so, the hero who changes for the better as a result of his love for the virtuous heroine ultimately perpetuates “the fantasy that the survivalist ideology of our time can be countered by reformed heirs from the higher social orders,” to borrow Yi’s words.

In any case, such a rich man/poor woman setup works well for a romantic comedy, since the barriers of class and gender provide a satisfying obstacle for the protagonists to overcome. But as enjoyable as it can be to watch a rich and handsome but morally corrupt man redeem himself by completely upending his life for a relatable heroine, this type of story gives all the agency to its hero. To return to Yi’s argument, although both protagonists suffer at the hands of an unjust system, the working-class heroine faces an existential struggle for survival that she cannot opt out of, while the upper-class hero chooses to enter a dilemma that tests his integrity. In a neoliberal system invested in the appearance of meritocracy without providing real pathways for social mobility, rescue by an ultra-wealthy man becomes the only escape for a woman oppressed by economic and gender inequality.

But the times have shifted. Since the late 1980s, South Korean women have increasingly challenged oppressive gender norms and gained legal rights. Economic pressures in the aftermath of the 1997 IMF crisis also led more women to enter the workforce. Mirroring global trends, Korean women are increasingly vocal about the pressures they deal with when trying to balance career and family. Both men and women are searching for creative ways to change the norms around partnership and childrearing so as to make them more equitable and sustainable. There is also growing awareness about the kinds of gendered violence and harassment that women face in their everyday lives.

Korean media reflects these shifts, as K-drama protagonists have evolved alongside these broader cultural conversations. Over the last decade, K-drama heroines have gotten sharper and the heroes softer. We are seeing more smart, successful, and flawed female leads get their own narrative arcs, while what K-drama fans used to refer to as “beta heroes” are no longer remarkable enough to require that descriptor.

Do we still see the Candy/chaebol romance? Absolutely—and I would even say it is making a comeback. But even in dramas that adopt this basic setup, we see less of the aggressive—even abusive—behaviors from male leads that were perceived as romantic in the early 2010s. If Secret Garden (2010) were made today, would Kim Joo-won still have essentially stalked Gil Ra-im, pestering her at her workplace and interfering in every aspect of her life whether she wanted it or not? Would the show still include that infamous scene where Joo-won pushes a reluctant Ra-im down onto a bed and forcibly kisses her until she stops struggling, all while a romantic score swelling in the background suggests to the audience that actually, she is loving this? I doubt it.

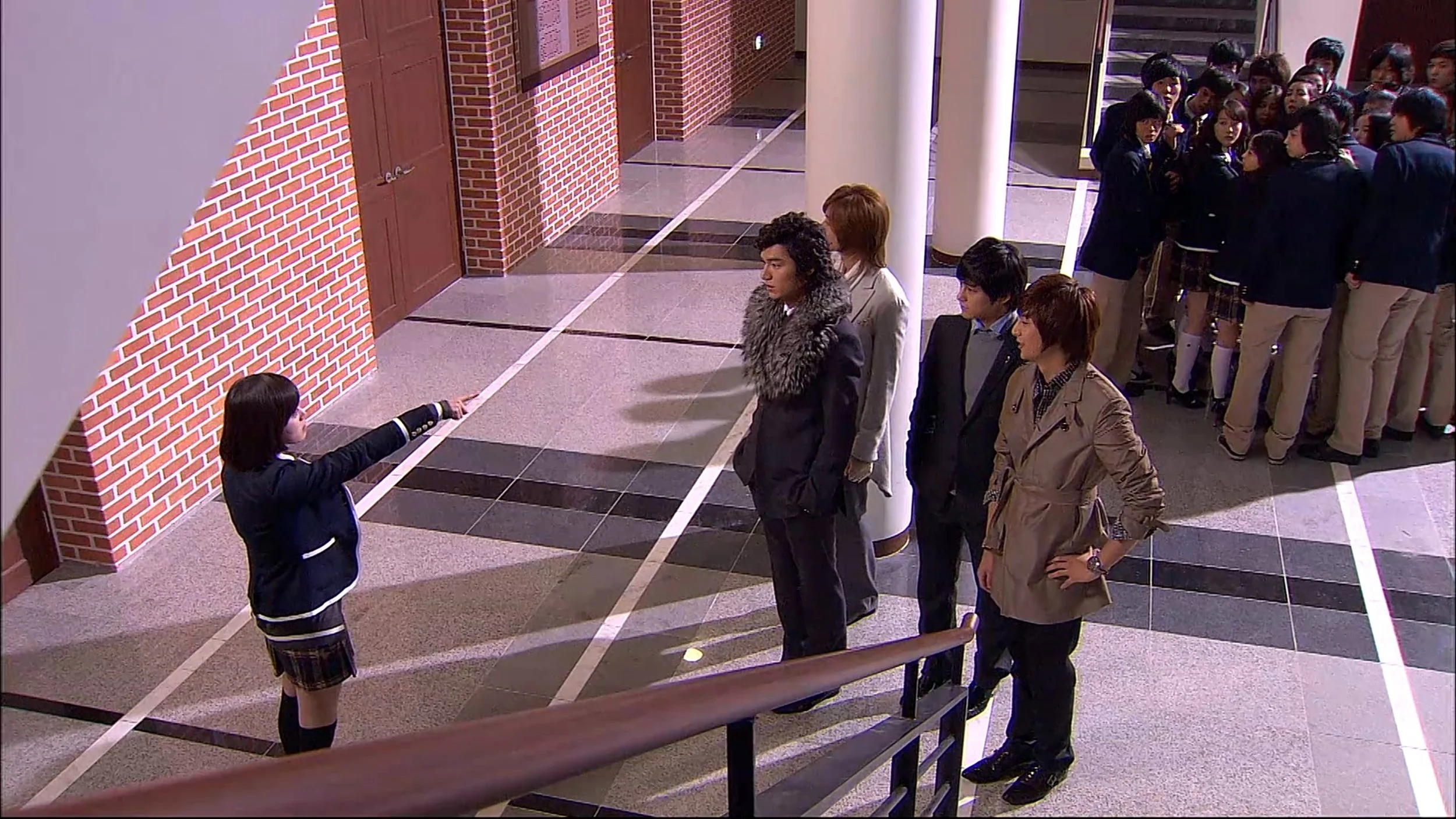

A quick comparison between Heirs (2014) and Doctor Slump (2024) illustrates how the romantic couple dynamic has shifted. In the earlier K-drama, both the hero and the second male lead continuously harass and spy on the heroine until she miserably gives in and picks one of them. Contrast this with Doctor Slump, made 10 years later with leading actors who also appeared in Heirs. In this later story, the hero Yeo Jeong-woo respects, supports, and validates the heroine Nam Ha-neul at every turn, even though the pair were rivals in high school. When they meet again as adults, Ha-neul has just quit her prestigious but stressful job as an anesthesiologist due to burnout, while Jeong-woo’s successful plastic surgeon career has unraveled following a public scandal (yes, it involves a murder). They quickly overcome their leftover animosity from childhood and bond over their mutual “slump.” Jeong-woo hangs out with Ha-neul each time she becomes overwhelmed by all the free time she suddenly possesses. As she figures out what she wants to do next, he cheers her on and even declines an opportunity to restart his own career so that he can be available to support her. Fittingly, the actor playing Jeong-woo (Park Hyung-sik) sings a song titled “Lean on Me” for the drama soundtrack. In the chorus, he croons, “lean on me so you won’t fall / I’ll come slowly closer so you won’t hurt alone.”

Doctor Slump is not an outlier. In general, romantic comedies have moved toward safer and more supportive relationships between their leads. Take the illustrative first meeting between Oh Mi-joo and Ki Seon-gyeom in Run On (2020). They accidentally knock into each other in the street, which causes Mi-joo’s gun lighter to fall out of her bag. Since the lighter looks just like a gun, Seon-gyeom ends up using it to scare off a male acquaintance who is physically threatening Mi-joo. Seon-gyeom himself does not ever pose a threat to Mi-joo. In fact, as a victim of domestic violence from his father, Seon-gyeom is vehemently opposed to interpersonal violence of any kind.

The gun lighter in Run On can be read as a meta-commentary on the evolution of the romantic dynamic in K-drama rom-coms. What initially appears to be an instrument of violence is not actually violent; it even becomes a protective device for warding off external threats that might harm the female lead. In this displacement of gendered violence from the realm of intimate relationships to a more external one, we can also trace the ideological impulse behind the murder rom-com, a point to which I will return later.

Murder as a Narrative Device

In the revamped rom-com where the protagonists are no longer kept apart by the deep divide in moral character (the tyrannical hero and the saintly heroine), murder becomes a useful narrative device. The threat that it poses can simmer in the background, emerging in the final act as a way for the protagonists to prove their love for each other and unite around a common goal.

Still, murder rom-coms are hard to pull off successfully. Poorly executed murder rom-coms create tonal whiplash and kill the romantic vibes that audiences came for. Many fans are tired of the subgenre, and I must confess to a similar sense of fatigue. Paroma Chakravarty, my co-host on the Dramas Over Flowers podcast, conducted an informal poll about the polarizing 2023 rom-com King the Land. Multiple respondents said that they enjoyed the show for its refreshing lack of murder.

When a murder plot is clumsily shoehorned in to stretch out a story, or introduced as a red herring to make the protagonists mistrust each other in a way that contradicts their characterization, it derails the romance and makes it harder to root for the couple. In My Lovely Liar (2023), for instance, the male protagonist Kim Do-ha is haunted by the death of his ex-girlfriend, whose murder he had been falsely accused of. Even though the female protagonist Mok Sol-hee (Kim So-hyun) possesses the magical ability to detect lies, the drama does not use her gifts as a reason for the couple to collaboratively investigate the murder but instead wastes entire episodes on Do-ha running into danger blindly trying to discover the truth on his own. Where the murder mystery could have been a vehicle for character and relationship development, it instead distracts from the central romance and ultimately leaves us wondering why this couple even belongs together.

When executed effectively, however, the murder plot becomes essential to the character arc of one or both of the protagonists, who undergo internal transformation as a result. After all, romance is, at its core, an exploration of how two people learn to meet each other emotionally, so its highest stakes are always internal. Introducing a shared enemy only works when that conflict reveals something deeper about who the protagonists are and what they mean to each other.

One example of a successful murder rom-com is the 2023 Crash Course in Romance, which weaves its murder plot into the emotional backstory of the male protagonist Choi Chi-yeol. The killer is connected to one of Chi-yeol’s former students who died by suicide due to overwhelming academic pressure. In the show’s present timeline, Chi-yeol remains traumatized and is unable to eat or sleep properly. The female protagonist Nam Haeng-seon provides a source of comfort because her food turns out to be the only thing he can keep down; later, the two emotionally connect and fall in love. Feeling pushed aside, Chi-yeol’s assistant Ji Dong-hee engages in violence toward the women in Chi-yeol’s life—he vandalizes Haeng-seon’s banchan shop and even assaults and kidnaps her daughter, who goes to the cram school where Chi-yeol teaches. Later, we find out that Dong-hee is actually the younger brother of Chi-yeol’s former student.

In Crash Course in Romance, murder functions to critique South Korea’s brutal education system and draw attention to the extreme pressures felt by parents and their children to stay academically competitive. Under such a system, only the wealthiest parents can provide the investment of time and resources that will give their children a fighting chance. The unchecked desire for academic excellence and for the material and social capital that such academic excellence is expected to generate leaves a literal trail of bodies in Crash Course in Romance: Dong-hee’s sister commits suicide after confessing that their mother had pressured her to cheat; Dong-hee kills his own mother, whose obsession with academic success led to her abusing him; in the end, Dong-hee also takes his own life. Much, though not all, of the violence in the drama is experienced by women, pointing to women’s particular vulnerability within such social structures. Tellingly, this drama achieved high ratings in South Korea where it resonated with viewers, while international fans who lacked the cultural context complained about the “unnecessary murder plot.”

Another example of a rom-com that successfully incorporates thriller elements is Suspicious Partner (2017). Eun Bong-hee, a law firm intern who is falsely accused of murdering her ex-boyfriend, must work with Noh Ji-wook, the attorney in her firm, to track down the real killer and clear her name. Part workplace romance and part legal procedural, the drama successfully balances its various genre elements, effectively using the case of the week to reflect and develop the romantic relationship between its protagonists.

At the center of the story is the murder case that Bong-hee finds herself ensnared in and the sexual violence that it brings to light. It turns out that the real culprit killed the men who had gang-raped the girl he liked, and then killed even more people to cover up those murders. The murderer is fighting gendered violence, but his unchecked vengefulness fails to discriminate between the innocent and the guilty. Meanwhile, the protagonists take on the much more difficult task of trying to make a deeply flawed justice system live up to its own stated ideals.

By making the central legal case one that deals with rape and its aftermath, Suspicious Partner foregrounds questions of consent, gendered violence, and how romantic partners navigate power and trust. In the process, Bong-hee and Ji-wook go from work “partners” who are “suspicious” of each other to romantic “partners” who can trust each other. In this regard, the show ultimately displaces the threat of intimate partner violence, safely locating that violence within an external source whose key function is to bring the lovers closer together. Yet, there is a strong element of wish fulfillment at play here. As women, whose real-life romantic relationships are too often marked by real danger, we wish for our rom-coms, at least, to be safe from violence.

A Cultural Trick Mirror

Women, who comprise the majority of rom-com producers and consumers, are keenly aware of how difficult and even dangerous it is to exist within patriarchal Korean society. A 2018 survey by South Korea’ s Broadcast Writers Union estimated that while 94.6 percent of the industry’s screenwriters are women, there is no guaranteed paid maternity leave for writers who become mothers. South Korea ranks 94th in global indexes of gender equality and has the largest gender wage gap among OECD countries. Although the overall crime rate is low due to gun control laws, South Korea has one of the world’s highest gender ratios for homicide victims: more than 50 percent of reported homicide victims and more than 90 percent of the victims of violent crime are women. Women must be constantly on the lookout for molka (the Korean term for spy cameras) in both public and private spaces; sometimes, these cameras are even planted in their homes by men they thought they could trust. Sex crimes and stalking are rarely punished, but even when they are, consequences often amount to slaps on the wrist. Women are so wary of the violence that can come from trying to end a relationship that they have dubbed successfully doing so a “safe breakup.”

All of this shows up in Korean popular media. Scenes of a woman discovering a molka in her living room (Business Proposal [2022]) or in a public bathroom (Not Others [2023]) have become so commonplace in K-dramas (even in otherwise light-hearted rom-coms) that they are no longer remarkable. Intimate partner violence is frequently depicted in romance dramas (Marry My Husband [2024]) and also openly discussed on variety shows. True crime shows have also become increasingly popular in Korea and especially among young women, leading to heightened vigilance around crimes that they are especially vulnerable to.

While progressive mainstream narratives around gender have increasingly emerged, the past few years have also seen an intense and sustained anti-feminist backlash. Catering to an increasingly vocal demographic of young men who claim to have been victimized and oppressed by women, the recently impeached former South Korean president Yoon Suk Yeol denied the existence of structural sexism and promised to abolish the Ministry of Family and Gender Equality during his presidential campaign in 2022. In this climate, crimes against women continue to be systematically dismissed or underpunished by both the legal system and the broader public.

How should we understand the murder rom-com against this cultural backdrop? It seems that the subgenre, largely written by and for women, gives voice to gendered violence even as it offers consolation for a reality that has failed to live up to women’s dreams. Like a trick mirror, a murder rom-com reflects the fantasy that women wish were true: that even if gendered violence persists, it is mostly committed by strangers with obvious bad vibes. By turning the perpetrators into uncomplicated villains who can be safely eliminated, the murder rom-com keeps its romantic heroes aspirational. For women viewers living in a world where the threat of violence and harassment from men is ever present, there is comfort and pleasure in knowing that in this story, the hero is a trustworthy protector—and the violence is coming from outside the house.

Despite appearances, perhaps not much has changed since the Candy/chaebol romances of the 1990s and 2000s. If, in those dramas, a poor woman can only transcend class boundaries by relying on a wealthy man, in today’s murder rom-coms, it is still the man who provides the most certain bulwark against the existential threats that mark a woman’s lived reality.

A New Life for Candy

Korean popular media, whether it be K-drama, K-pop, or Korean film, rarely confines its storytelling to a single theme, tone or genre. Even the darkest revenge melodrama will have moments of humor, almost every narrative genre—family drama, legal thriller, workplace comedy, or something else—involves a love story, and I challenge you to find a show with no commentary on class inequality.

K-dramas also have never been afraid to try new things. Since the time travel drama emerged in the early 2010s, we have not looked back—the genre has not only become a staple but is evolving. Recently, we got two time travel contract marriage revenge melodramas within the span of mere months: Perfect Marriage Revenge concluded in December 2023 and Marry My Husband premiered in January 2024. One was, if I may say so, perfect and one was kind of a train wreck, but they were both extremely watchable.

Like anything else, K-dramas go through trends, and sometimes those trends become popular enough to crystallize into full-blown subgenres. I think the murder rom-com is here to stay, though perhaps recent trends indicate that some in the industry are starting to find it stale. In the last couple of years, a wave of dramas has resurfaced the old tropes: the tyrannical boss overcome by his long-suffering secretary; the poor orphan facing off against the powerful chaebol corporation; the innocent and self-sacrificing woman who falls in love with a man too emotionally broken to express his own feelings. Yet, the best of these shows tend to include some twist that refreshes these familiar scenarios. (If you have not yet seen this year’s perfect gender-reversed boss/secretary romance Love Scout, drop everything and watch it now!)

Perhaps we’re at the beginning of a new cycle . . . and of course, everything old is new again. Ə